Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to understand and describe:

- Piaget’s concrete operational stage of cognitive development

- Memory and cognitive processes

- The nature of intelligence

- The Influence of heredity, culture, and the environment

Introduction

Thought processes that become more logical and organized when dealing with concrete and increasingly more abstract information. Children at this age understand concepts such as past, present, and future, giving them the ability to plan and work toward goals. Additionally, they can process complex ideas such as addition and subtraction and cause-and-effect relationship.

For most children, school becomes a context for development and where their abilities are assessed and reported on. Throughout childhood and beyond there are many factors which influence an individual’s overall cognitive development. These include their socioeconomic status, parenting, their lived experiences and individual differences in cognitive process, and these differences predict both their readiness for school, academic performance, and testing in school (Prebler, Krajewski, & Hasselhorn, 2013, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

The Continuum of Development describes a number of skills pertaining to children’s cognitive development domain during middle childhood. These include an increasing ability to self-regulate, an interest in games with rules and further development of mathematical skills such as describing patterns, spatial reasoning, creating and using maps (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

For Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) having an understanding of developmental milestones in cognitive development at this age supports our expectations. We can adapt and adjust the language we use, how we structure activities, interventions, and our own approach to working with young people and families. When working with families, we can encourage caregivers to support healthy cognitive development through reading, games, and other great resources.

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Cognitive Operational Thought

As children continue into elementary school, they develop the ability to represent ideas and events with more logic and flexibility. Piaget called this period the concrete operational stage because children mentally “operate” on concrete objects and events.

The concrete operational stage is defined as the third in Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. This stage takes place around 7 years old to 11 years of age and is characterized by the development of organized and rational thinking. Piaget (1954a, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development, because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought. The child is now mature enough to use logical thought or operations (i.e. rules) but can only apply logic to physical objects (hence concrete operational). Children gain the abilities of conservation (number, area, volume, orientation) and reversibility (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

These skills allow children to solve problems more systematically than before, and therefore to be successful with many academic tasks. In the concrete operational stage, for example, a child may unconsciously follow the rule: “If nothing is added or taken away, then the amount of something stays the same.”

Let’s look at the following cognitive skills that children typically master during Piaget’s concrete operational stage 6:

Seriation: Arranging items along a quantitative dimension, such as length or weight, in a methodical way is now demonstrated by the concrete operational child. For example, they can methodically arrange a series of different-sized sticks in order by length, while younger children approach a similar task in a haphazard way (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Classification: As children gain more experiences and their vocabularies expand, they build schema and can recognize and perhaps describe attributes and organize objects in many different ways. They also understand classification hierarchies and can arrange objects into a variety of classes and subclasses.

Reversibility: The child learns that some things that have been changed can be returned to their original state. Water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again. But eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. School curricula around the world reflects children’s developing cognitive skills and educators are encouraged to provide opportunities for children to explore and demonstrate these new skills and increased awareness.

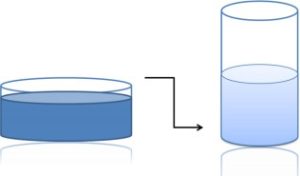

Conservation: In the chapter describing Piaget’s pre operational stage of cognitive development, you learned that a child in this stage would believe that if you were to fill a tall beaker with 8 ounces of water they would think that it was “more” than a short, wide bowl filled with 8 ounces of water. Children in the Concrete operational stage can understand the concept of conservation, which means that changing one attribute (in this example, height or water level) can be compensated for by changes in another attribute (width). Consequently, there is the same amount (conserved) of water in each container, although one is taller and narrower and the other is shorter and wider. Children in the pre operational stage may look at the attribute of height or depth and believe that the taller container has more water (depth) .

Figure 12.3: Beakers displaying the idea of conservation. (Image by Ydolem2689 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Decentration: Children in the concrete operational stage of development children no longer focus on only one dimension or attribute of any object (such as the height of the glass) and instead consider the changes in other dimensions and attributes also (such as the width of the glass). This allows for conservation to occur.

Image 12.4: Children looking at these glasses demonstrate decentration when looking at more than one attribute i.e. tall, short, and wide narrow. (Image by Waterlily16 is licensed under CC by-SA 3.0)

Identity: One feature of concrete operational thought is the understanding that objects have qualities or attributes that do not change even if the object is altered in some way. For instance, mass of an object does not change by rearranging it. A piece of chalk is still chalk even when the piece is broken in two (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Image 12.5: A broken egg is still an egg (Image bu John Liu is licensed under CC-BY 2.0)

Image 12.6: A deflated balloon is still a balloon. (Image is licensed under CC0)

Image 12.7: Broken chalk is still chalk. (Image from Pexels)

Transitivity: This refers to the ability to understand how objects are related to one another is referred to as transitivity or transitive inference. This means that if one understands that a dog is a mammal and that a boxer is a dog, then a boxer must be a mammal.

Image 12.8- Transitivity allows children to understand that his boxer puppy is a dog and a mammal. (Image by Martin Vorel is in the public domain)

Memory Processes

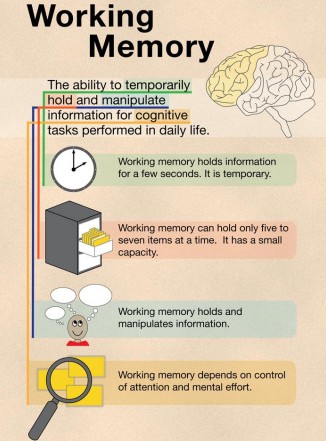

During middle and late childhood children make strides in several areas of cognitive function including the capacity of working memory, their ability to pay attention, and their use of memory strategies. Both changes in the brain and experience foster these abilities. In this section, we will look at how children process information, think and learn, allowing them to increase their ability to learn and remember due to an improvement in the ways they attend to, store information, and problem solve (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Image 12.10: Working memory expands during middle and late childhood. (Image by Anchor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA)

Working Memory: Research has suggested that both an increase in processing speed and the ability to inhibit irrelevant information from entering memory are contributing to the greater efficiency of working memory during this age (de Ribaupierre, 2002, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Changes in myelination and synaptic pruning in the cortex are likely behind the increase in processing speed and ability to filter out irrelevant stimuli (Kail, McBride-Chang, Ferrer, Cho, & Shu, 2013, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Attention: As noted above, the ability to inhibit irrelevant information improves during this stage of development with a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence (Vakil, Blachstein, Sheinman, & Greenstein, 2009, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Children also improve in their ability to shift their attention between tasks or different features of a task (Carlson, Zelazo, & Faja, 2013, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). A younger child who is asked to sort objects into piles based on the type of object, car versus animal, or color of the object, red versus blue, would likely have no trouble doing so. But if you ask them to switch from sorting based on type to now having them sort based on color, they would struggle because this requires them to suppress the prior sorting rule. An older child has less difficulty making the switch, meaning there is greater flexibility in their attentional skills. These changes in attention and working memory contribute to children having more strategic approaches to challenging tasks.

Memory Strategies: Bjorklund (2005, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) describes a developmental progression in the acquisition and use of memory strategies as children progress through elementary school. Examples of memory strategies include rehearsing information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, such as “i” before “e” except after “c”, or inventing acronyms, or pneumonic device such as “roygbiv” to remember the colors of the rainbow. In a longitudinal study Schneider, Kron-Sperl, and Hünnerkopf (2009, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) reported a steady increase in the use of memory strategies from ages six to ten. Moreover, by age ten many children were using two or more memory strategies to help them recall information. Schneider and colleagues found that there were considerable individual differences at each age in the use of strategies and that children who utilized more strategies had better memory performance than their same-aged peers.

Cognitive processes

As children enter school and learn more about the world, their knowledge base expands, and becomes more refined as they develop more categories for concepts (Berger, 2014, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). They learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information.

Metacognition: Refers to the knowledge we have about our own thinking and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our own cognitive processes (Bruning, Schraw, Norby, & Ronning, 2004, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Children in this developmental stage can’ think about thinking’ and are better able to evaluate their performance of a task and the level of difficulty of the task. As they become more aware of their abilities, they can set goals and adapt studying strategies to support their success.

Critical thinking

According to the Ontario Mathematics Curriculum (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2020) critical thinking can be described as: “the process of thinking about ideas or situations in order to understand them fully, identify their implications, make a judgement, and/or guide decision making.”

Critical thinking includes a number of skills such as questioning, predicting, analysing, synthesizing, examining opinions, identifying values and issues, detecting bias, and distinguishing between alternatives (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2020). It is important to teach children these thinking skills so they can become individuals who can engage in detailed examination of beliefs, courses of action, and evidence, and evaluate information to make informed decisions that can have a positive impact on the world. Critical thinking involves better understanding a problem through gathering, evaluating, and selecting information, and also by considering many possible solutions. Ennis (1987, as cited in Ontario Ministry of Education, 2020) identified several skills useful in critical thinking. Metacognition is essential to critical thinking because it allows us to reflect on the information as we make decisions and move beyond superficial conclusions to a deeper understanding of the issues being examined (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2020).

Intelligence and learning

Piaget described human cognition as developing in distinct and somewhat discontinuous stages while other researchers (e.g. Sternberg 1997; 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) describe cognitive development as more continuous in nature.

Many tools to measure and standardize intelligence testing have been created since the early 20th century. These include tools such as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test (thought of as the first intelligence test developed by French and American psychologists) and the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale (developed in the late 30s and includes versions for individuals with a variety of verbal and nonverbal skills from preschool all the way to adulthood.

Intelligence tests and psychological definitions of intelligence have been heavily criticized since the 1970s for being biased in favour of Anglo-American, middle-class respondents and for being inadequate tools for measuring non-academic types of intelligence or talent.

Intelligence changes with experience, and intelligence quotients or scores do not reflect that ability to change. What is considered smart varies culturally as well, and most intelligence tests do not take this variation into account. For example, in the West, being smart is associated with being quick. A person who answers a question the fastest is seen as the smartest, but in some cultures being smart is associated with considering an idea thoroughly before giving an answer. In these cultures, a well-thought out, contemplative answer is the best answer (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019). This view is also seen in Indigenous cultures were children are taught to be mindful about the words being used before answering a question.

Learning and intelligence on a spectrum

Learning is seen as occurring on a spectrum, and newer evaluative tests account for different types of learning.

An alternative view of intelligence is presented by Sternberg (1997; 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Sternberg offers three types of intelligences, such as analytical (or academic), creative (experiential), and practical (contextual).

Another champion of the idea of specific types of intelligences rather than one overall intelligence is the psychologist Howard Gardner (1983, 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) who argued that it would be evolutionarily functional for different people to have different talents and skills, and proposed that there are nine intelligences that can be differentiated from each other, and these are also forms of intelligence. A high IQ does not always ensure success in life or necessarily indicate that a person has common sense, good interpersonal skills, or other abilities important for success.

Gardner investigated intelligences by focusing on children who were talented in one or more areas. In Gardner’s original work, and over the years, he identified different intelligences based on other criteria including a set developmental history and psychometric findings, including linguistic, musical, spatial, kinesthetic, naturalistic, and existential intelligence.

Intellectual Exceptionalities

One end of the distribution of intelligence scores is defined by people with very low IQ. Intellectual disability (or intellectual developmental disorder) is assessed based on cognitive capacity (IQ) and adaptive functioning. The severity of the disability is based on adaptive functioning, or how well the person handles everyday life tasks. One example of an intellectual developmental disorder is Down syndrome (also known as Trisomy 21), a chromosomal disorder caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome. The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at approximately 1 per 700 births, and the prevalence increases as the mother’s age increases (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). People with Down syndrome typically exhibit a distinctive pattern of physical features, including a flat nose, upwardly slanted eye, a protruding tongue, and a short neck.

A particular vulnerability of people with low IQ is that they may be taken advantage of by others, and this is an important aspect of the definition of intellectual developmental disorder (Greenspan, Loughlin, & Black, 2001, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Figure 12.12: Down syndrome is caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome. (Image by Vanellus Foto is Licensed under CC BY-SA)

Heredity, Culture, and the Environment

Indigenous children are not seen as having disabilities, they are considered as having different gifts that others may not have. They are regarded as being brought to the mother and father, to the community, and other family members to show them something. It is seen in a wholistic way. Take for instance in the case of someone who has impaired vision, their other senses are higher than someone who does not have that exceptionality.

Many cultures have different views on learning, intelligence, and cognitive development. The environment a child grows up in can also influence development, beyond curiosity, experience, and physical space. Heredity and biology can mean children are predisposed to certain experiences, but this is only a small piece. Other factors, such as protective factors, resilience, and opportunities to thrive can expand a child’s experience.

A child doesn’t need expensive toys in order to thrive, they benefit from being able to use their imagination! Unicef (2022) has guidelines for child development and education, and they outline that “educational environments must be safe, healthy and protective. Learning environments must be a haven for children to learn and grow, with respect for their identities and varied needs… [and] promotes inclusiveness, gender-sensitivity, tolerance, dignity and personal empowerment.” Want to read more? Check out their website: https://www.unicef.ca/en/discover/education

Summary

- Piaget’s concrete operational stage of cognitive development

- Memory and cognitive processes

- The nature of intelligence

- The Influence of heredity, culture, and the environment

References

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Birth defects. Facts about down syndrome. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/downsyndrome.html

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “ELECT”. Retrieved from https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (2020). Ontario curriculum grades 1-8: Mathematics. Retrieved from https://www.dcp.edu.gov.on.ca/en/curriculum/elementary-mathematics

OER Attributions

Content from this reading has been adapted from the following sources:

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed (2022) by Tanya Pye; Susan Scoffin; Janice Quade; and Jane Krieg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, and Johnson is shared under a CC BY license, except where otherwise noted.