Cognitive Development in Preschool Children

Chapter Objectives

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe theories relating to cognitive processing, learning, and memory

- Define how language and communication develop in pre-school children

- Identify stages of how drawings develop

Introduction

Cognitive development is happening at a rapid pace in preschool children!

The understanding we have of cognitive development is advancing on many different fronts. One exciting area is linking changes in brain activity to changes in children’s thinking (Nelson et al., 2006, as cited in Leon, n.d.). While there is a lot of brain development and maturation that takes place before a baby is even born, the brain continues to develop throughout childhood into adulthood! (Pye, Scoffin, Quade, & Krieg, 2022).

For example, a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which is located at the front of the brain and is particularly involved with planning and flexible problem solving, continues to develop throughout childhood (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006, as cited in Leon, n.d.), throughout adolescence, and into emerging adulthood (Johnson, Blum & Giedd, 2009).

For Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) this information informs our understanding, as well as provides a general benchmark around cognitive development.

In our readings dedicated to Applied Human Development, we learned that CYCPs “integrate current knowledge of human development with the skills, expertise, objectivity and self awareness essential for developing, implementing and evaluating effective programs and services” (Association for Child and Youth Care Practice, 2010). Knowing the typical benchmarks for any given area of developmental age and stage, we can recognize exceptionalities, determine how to adapt or adjust our approach, and start where the young person is at.

The preschools years are a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning some basic principles about how the world works, they hold some interesting ideas. For example, while adults have no concerns with taking a bath, a child of three might genuinely worry about being sucked down the drain. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size and distance are not easy to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.

Especially in the preschool years, caregivers and adults may start noticing variations to the milestones theorists have described as ‘standard.’ We know, as CYCPs, that there is no standard, and every individual is unique. Throughout your mental health -and other courses, you will learn about exceptionalities. One example that highlights variations in cognitive development, is that of neurodiversity, which we explore later in this reading.

The following reading is a summary of the cognitive skills that develop during the preschool years.

Preschool cognitive skills

Core skills

Curiosity

- children continue to observe their world

- ask questions

- develop and test their theories about how things work

Thinking

- master new ways of describing and making meaning of their experiences

- reasoning is more logical, they solve problems by collecting and organizing information, reflecting on it, drawing conclusions and communicating their findings with others – through classifying and seriating

- understanding size, time, distance, fact and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years

Language

- increased verbal abilities allow them to use spatial terms and positional words such as behind, inside, in front of, between

- can follow directions

- begin creating and using maps

Math

- Increasing understanding of numeracy – includes:

- counting in meaningful ways to determine quantity

- comparing quantities

- completing simple number operations using number symbols

- Explore ways to represent numbers, e.g., tally marks

Thinking and reasoning

HealthLink BC (2025) has a good summary of what’s taking place at this age:

Most children:

- Know their own name, age, and gender

- Follow 2- to 3-step instructions, such as “pick up your doll and put it on your bed next to the teddy bear”

- Grasp the concept of “two.” E.g., they understand when they have two cookies rather than one, but usually aren’t yet able to understand the concept of higher numbers

By age 5:

- Know their address and phone number

- Recognize most letters of the alphabet

- Can count 10 or more objects

- Know the names of at least 4 colours

- Understand the basic concepts of time

- Know what household objects are used for, such as money, food, or appliances

Let’s explore some specific theories that focus on cognitive development, then we’ll move into language and memory.

Piaget’s Preoperational Intelligence

Piaget’s second stage is the preoperational stage which is from approximately 2 to 7 years old. In this stage, children can use symbols to represent words, images, and ideas, which is why children in this stage engage in pretend play.

The word operational means logical; children are learning to use language and to think about the world symbolically. Their logic is based on their own personal knowledge of the world so far, rather than on conventional knowledge.

Children begin to use language in the preoperational stage, but can’t yet fully understand adult logic or mentally manipulate information.

Piaget believed that in a quest for cognitive equilibrium, we use schemas (categories of knowledge) to make sense of the world. And when new experiences fit into existing schemas, we use assimilation to add that new knowledge to the schema. But when new experiences do not match an existing schema, we use accommodation to add a new schema.

During early childhood, children use accommodation often as they build their understanding of the world around them.

Preschoolers begin to use objects to represent other things – this is known as mental representation. These new skills support the emergence of make-believe play.

For example:

- A child’s arms might become airplane wings as he zooms around the room

- A child with a stick might become a brave knight with a sword

- A block can be a phone

Cartoons and animation frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities, so children may also think that a small gardening tool could grow up to be a full-size shovel. This is called animism, attributing life-like qualities to inanimate objects. The chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired.

At this stage, children tend to think that everyone thinks, feels, and sees things in the same way as the child, which is known as egocentrism. The child is not able to take the perspective of others.

For example: Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes her brother Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too. However, his mom reminds him that Keiko’s favourite character is Groot, yet Kenny insists they buy the Iron Man figure!

Piaget developed the Three-Mountain Task to determine the level of egocentrism displayed by children. Children view a 3-dimensional mountain scene from one viewpoint, and are asked what another person at a different viewpoint would see in the same scene.

Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own view, rather than that of the doll. However, children tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way, known as a classification error. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.

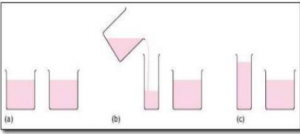

Conservation errors – Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, & Johnson, 2021). As seen in figure 9.1 below, the child is shown two glasses (as shown in a) which are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually, the child agrees they have the same amount. The researcher then pours the liquid from one glass to a taller and thinner glass (as shown in b). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller. The child has concentrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Figure 9.1: Piagetian liquid conservation experiments. (Image by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Pretend play

Pretending is a favourite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land! Image 9.5 is an example of pretend play.

Pretend play is a form of communication – children communicate with others using language gestures and symbolic objects to tell and retell stories (Berk & Winsler, 1995, as cited in Pye et al., 2022). Social competence, emotional and attention self-regulation and the ability to communicate with others are foundational to all types of learning and are best developed in play-based environments (Barnett et al., 2006; Ziegler, Singer & Bishop-Josef, 2005; Kagan & Lowenstein, 2004, as cited in Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

According to Piaget, children’s pretend play helps them solidify new schemes they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflects changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they take on roles, examine perspectives, pretend, and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007, as cited Paris et al., 2021). In their play they make meaning of their lived experiences and explore possibilities as they consider ‘what is’ and ‘what if’?

“The developmental literature is clear: play stimulates physical, social, emotional and cognitive development in the early years. Children need time, space, materials and the support… [of caregivers and professionals]”

Hewes (2006, as cited in Pye et al., 2022).

Indigenous Perspectives

This is the perfect age to introduce Indigenous Storytelling with role playing the animals in the story. Let them change the story and have fun with it. Children will see themselves in the story. This relates to what Piaget says: “In their play, they make meaning of their lived experiences and explore possibilities as they consider ‘what is’ and ‘what if’?” Plenty of outdoor play will help to connect children to the land.

At this age, children also have to have clear directions in order to complete what they are asked to do. For example, if the child is not looking at you. You say listen to me. The child says “I am listening to you.” The educator has to be precise in what they are asking of the child. It is important to note that a lot of Indigenous children might not look you in the eyes. This is a cultural thing.

Indigenous Storybooks (n.d.) is a great project that provides resources available in Indigenous languages, English, and French. Check out: Indigenous Storybooks resources.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Development

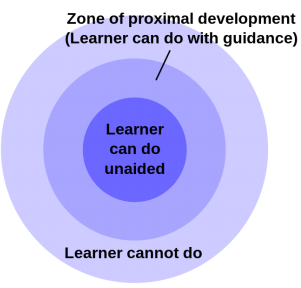

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

Lev Vygotsky’s best-known concept is the zone of proximal development (ZPD). Vygotsky stated that children should be taught in the ZPD, which occurs when they can perform a task with assistance, but not quite yet on their own. With the right kind of teaching, however, they can accomplish it successfully. A CYCP, teacher, or caregiver identifies a child’s ZPD and helps the child stretch beyond it. Then the adult (CYCP, teacher, or caregiver) gradually withdraws support until the child can then perform the task without assistance. Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching.

Scaffolding is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task.

Private Speech

Contrast with Piaget

Piaget was highly critical of teacher-directed instruction, believing that teachers who take control of the child’s learning place the child into a passive role (Crain, 2005, as cited in Paris et al., 2021). Further, teachers may present abstract ideas without the child’s true understanding, and instead they just repeat back what they heard. Piaget believed children must be given opportunities to discover concepts on their own. As previously stated, Vygotsky did not believe children could reach a higher cognitive level without instruction from more learned individuals. Who is correct? Both theories certainly contribute to our understanding of how children learn.

Neo-Piagetians

As previously discussed, Piaget’s theory has been criticized on many fronts, and updates to reflect more current research have been provided by the Neo-Piagetians, or those theorists who provide “new” interpretations of Piaget’s theory. Morra, Gobbo, Marini and Sheese (2008, as cited in Paris et al., 2021) reviewed Neo-Piagetian theories, which were first presented in the 1970s, and identified how these “new” theories combined Piagetian concepts with those found in Information Processing. Similar to Piaget’s theory, Neo- Piagetian theories believe in constructivism, assume cognitive development can be separated into different stages with qualitatively different characteristics, and advocate that children’s thinking becomes more complex in advanced stages. Unlike Piaget, Neo-Piagetians believe that aspects of information processing change the complexity of each stage, not logic as determined by Piaget.

Neo-Piagetians propose that working memory capacity is affected by biological maturation, and therefore restricts young children’s ability to acquire complex thinking and reasoning skills. Increases in working memory performance and cognitive skills development coincide with the timing of several neurodevelopmental processes. These include myelination, axonal and synaptic pruning, changes in cerebral metabolism, and changes in brain activity (Morra et al., 2008, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Myelination especially occurs in waves between birth and adolescence, and the degree of myelination in particular areas explain the increasing efficiency of certain skills. Therefore, brain maturation, which occurs in spurts, affects how and when cognitive skills develop. Additionally, all Neo-Piagetian theories support that experience and learning interact with biological maturation in shaping cognitive development (Lally & Valentine-French, 2019).

Children’s understanding of the world

Both Piaget and Vygotsky believed that children actively try to understand the world around them. More recently developmentalists have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world (Paris et al., 2021).

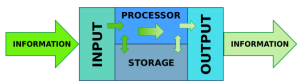

Information-Processing Theories

How we think and process information varies from person to person. The information-processing perspective derives from the study of artificial intelligence and explains cognitive development in terms of the growth of specific components of the overall process of thinking (Seifert & Sutton, 2009). Theories that focus on describing cognitive processes that underlie thinking at any one age and cognitive growth over time (Siegler, 2024). This is in contrast to Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, that are more linear and one must be achieved before the next. One of the main critiques of early cognitive theories is that achievement is lifelong, and always adapting and developing (Lumen Learning, 2019).

- Attention: Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory: Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing Speed: Improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood.

- Organization: Preschoolers are more aware of their own thought processes as they grow

Information-processing theories have become an influential alternative to Piaget’s approach. The theory assumes that even complex behaviour such as learning, remembering, categorizing, and thinking can be broken down into a series of individual, specific steps, and as a person develops strategies for processing information, they can learn more complex information. This perspective equates the mind to a computer, which is responsible for analyzing information from the environment.

Our brains are continuously taking information in, and we are many times unaware – meaning this is subconscious.

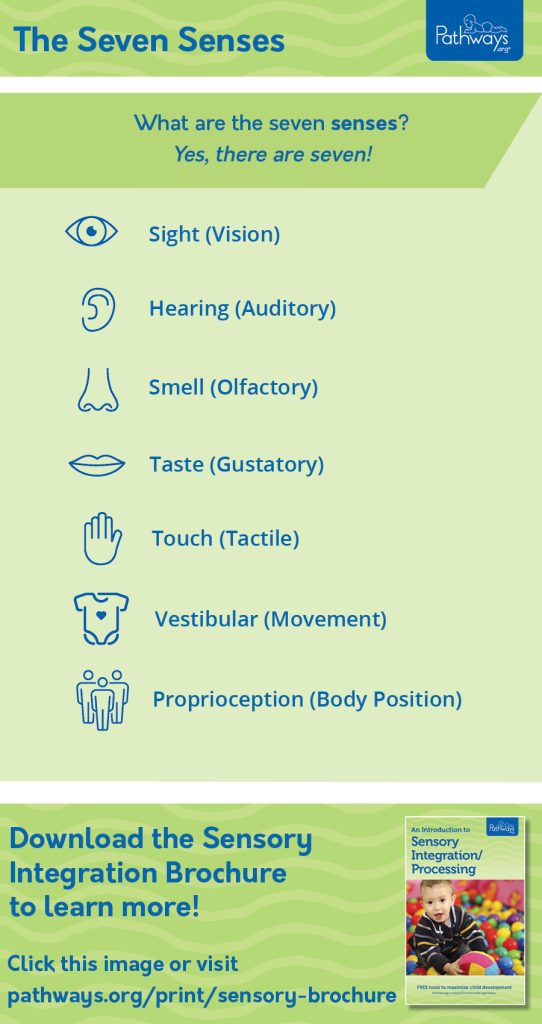

The information we take in comes from all the senses (see Figure 1; Pathways.org, 2023). These include things we can:

- See

- Smell

- Taste

- Touch

- Hear

There are also two senses relating to our body relating to:

- Body movement

- Proprioception (body position)

For more information on the senses and how we use them relating to development, visit: https://pathways.org/topics-of-development/sensory/ What might this mean for us in terms of our work with young people and families? How can we use this information in our practice?

The ability to use the various senses is fundamental to the information processed by our brains, as these are the sensory inputs. Not having one or more of our senses available to us means that other senses are heightened (no, not our spidey sense, unfortunately – and not quite to the extreme of someone like Daredevil… Again, that’s beyond the scope of this course!)

Language and Memory

Language

Language also supports (and is supported by) brain development.

A child’s vocabulary during the preschool years expands from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known.

The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese, tend to learn verbs more readily. But those learning less verb-friendly languages such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai, et al, 2008, as cited by Paris et al., 2021).

Language Milestones

| Typical age | Typical skill |

| 3 years |

|

| 4 years |

|

| 5 years |

|

Table 9.1: Language Milestones. Developmental Milestones by the CDC (2023) is in the public domain)

Want to learn more? Read: How you talk to your child changes their brain

Consider our work as CYCPs. How might our use of language encourage development?

Memory

Sensory memory (also called the sensory register) is the first stage of the memory system, and it stores sensory input in its raw form for a very brief duration; essentially long enough for the brain to register and start processing the information.

Studies of auditory sensory memory show that it lasts about one second in 2-year-olds, two seconds in 3-year-olds, more than two seconds in 4-year-olds, and three to five seconds in 6-year-olds (Glass, Sachse, & von Suchodoletz, 2008, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

Other researchers have also found that young children hold sounds for a shorter duration than do older children and adults, and that this deficit is not due to attentional differences between these age groups, but reflects differences in the performance of the sensory memory system (Gomes et al., 1999, as cited in Paris et al., 2021).

The second stage of the memory system is called short-term or working memory. Working memory is the component of memory in which current conscious mental activity occurs. It often requires conscious effort and adequate use of attention to function effectively.

The third stage in memory is long-term memory, which is also known as permanent memory. This includes:

- Declarative memories, sometimes referred to as explicit memories, are memories for facts or events that we can consciously recollect. Declarative memory is further divided into semantic and episodic memory.

- Semantic memories are memories for facts and knowledge that are not tied to a timeline

- Episodic memories are tied to specific events in time.

- Non- declarative memories, sometimes referred to as implicit memories, are typically automated skills that do not require conscious recollection

As we continue learning about cognitive development, we will explore memory and language further.

Information processing, learning, learning, and exceptionalities

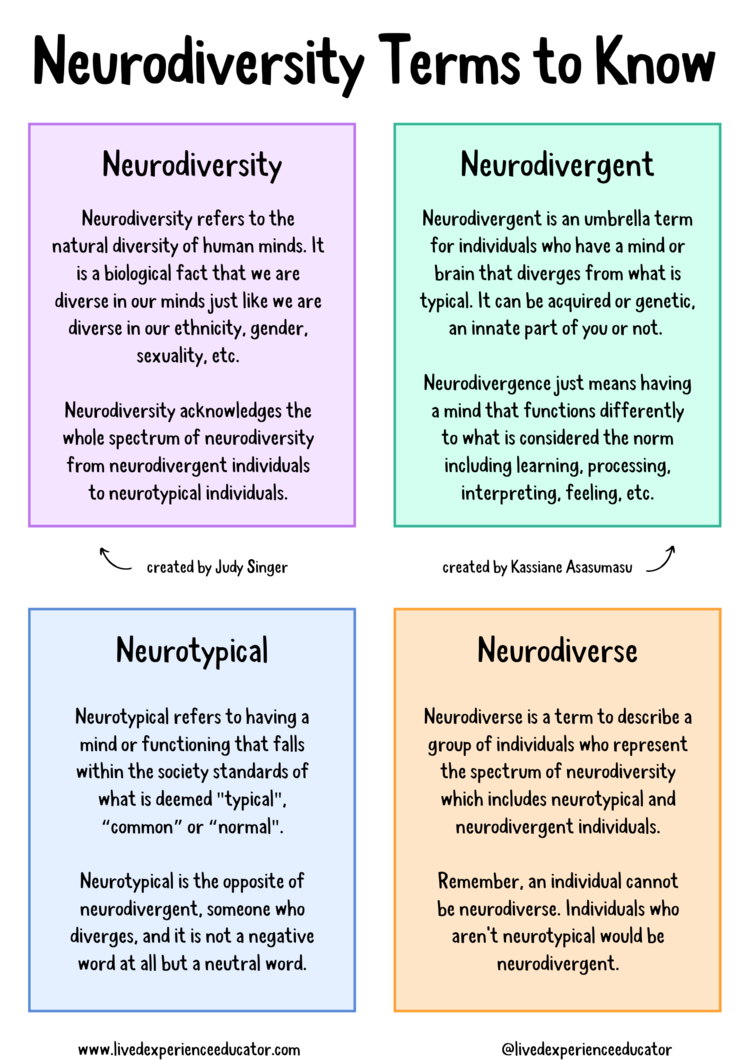

Our societal expectations of how the brain functions is based on often outdated research, limited in most cases to studies on Eurocentric boys or men (Alvares, 2011). Researchers, mental health professionals, and the medical community tend to use a neurotypical expectation of how the brain works, and what we can be expected to do – in terms of functioning, thinking, and other areas. These are individuals “who’s functioning meets the dominant societal norms” (Wise, 2019). You will recall from your Mental Health course that the medical model “identifies mental differences as ‘abnormalities, disorders, deficits, or dysfunctions.’ From this perspective, some neurominority states are treated as medical conditions that can and should be corrected” (Disabled World, 2022).

Current research is slowly becoming more inclusive, and this has allowed for a more thorough understanding of individual and natural differences in development, including what we know about the brain and how it is wired, known as neurodiversity (Child Mind Institute, 2024; Wise, 2019). This allows for different views of validating experiences, and not that there is a typical or expected way to think, or for brains to be wired. Image 4 highlights the various terms that are relevant to know, along with their differences:

To download a pdf. version of this file, go to the Lived Experience Educator website

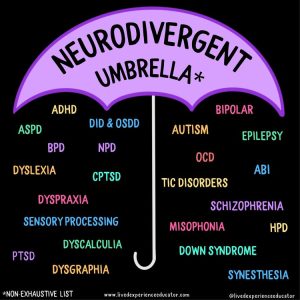

The term neurodivergent can be seen as an umbrella term – including many different categories, experiences, and diagnoses.

The Neurodivergent Umbrella

Some of the examples or types of neurodivergence that we will encounter as CYCPs in our work with young people and families include autism, dyslexia, epilepsy, various anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), Tourette syndrome (TS), Down Syndrome, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), various learning disabilities (LDs), and sensory processing disorder, to name a few. There are even more, and Image 9.10 lists more.

Learning disabilities (LDs) and exceptionalities like the ones listed above can impact “the way in which a person takes in, remembers, understands and expresses information” (Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario, 2015 ). We will continue to learn about exceptionalities and neurodiversity throughout the program; consider this a brief introduction.

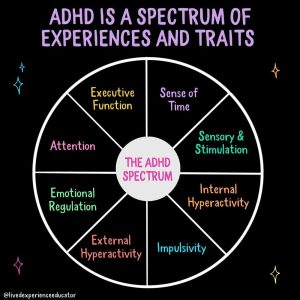

Many of these diagnoses exist on a spectrum – meaning individuals can have different traits and experiences- and others . For example, ADHD affects many areas of daily life as a result of how the brain is wired. See Images 9.11:

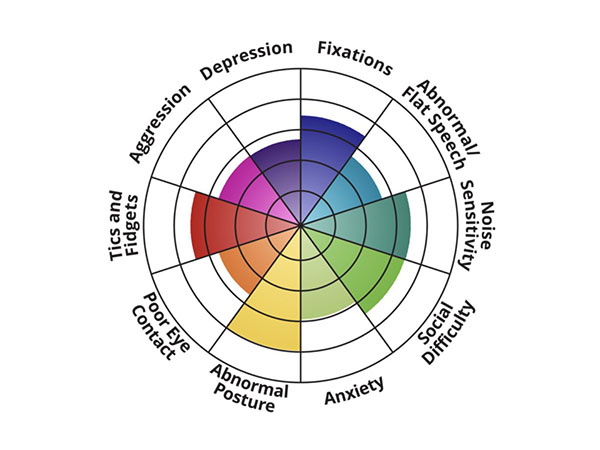

Using a wheel to visually display the traits and experiences – many of which overlap between diagnoses – is moving away from the spectrum visual – which is more linear, general, and implies more or less impact overall, rather than looking at the different areas. See Image 9.12 for another example.

These two images demonstrate the different areas that are impacted by the diagnoses; which are assessed using criteria from the DSM 5: TR by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other medical professional.

These are lifelong diagnoses that an individual does not outgrow – which some health professionals are still learning…

Want to learn more?

For more information and descriptions of exceptionalities and neurodivergent minds, visit the hyperlinks embedded in this section.

To learn even more, here are more resources for you to explore:

Neurodiversity is one of the many populations we can support as a CYCP. In schools, accommodations can be one resource available. Skill building is another resource, which we support through activities and interventions alongside other professionals and supports available.

You will learn more about exceptionalities in your Mental Health and Wellness courses throughout the program.

Play as Learning

After reviewing the content this week, consider how we as CYCPs might incorporate play.

Here are some suggestions, from the Ontario Ministry of Education (2014):

- Create learning environments and caring communities where children play collaboratively and participate together in the daily routines

- Use indoor and outdoor environments in distinctive areas for different types of play and engagement

- Take an active role in play with the children

- Promote play that offers challenge and that is within the child’s capacity (Zone of Proximal Development!) to master by creating opportunities for play where children can learn, practice and extend their skills

- Variety is key – allow for choice, and different opportunities

- Provide structured and unstructured (free play) so that children can select among types of social play, activities, projects and play areas

- Use play as an opportunity to model acceptance, respect, empathy and co-operative problem solving strategies: create situations that encourage children to co-operate; balance individual with group needs; provide experiences that expand children’s capacity to verbally exchange ideas and feelings with others where children learn from each other as well as adults

What are some activities you can think of that encourage play and cognitive development?

Last week we covered drawing, and the stages of drawing that highlight not only physical development, but cognitive development as well. Review the reading and participate in the activity in this week’s video lesson!

Summary

The many theories of cognitive development and the different research that has been done about how children understand the world has allowed researchers to study the milestones that children who are typically developing experience during the preschool years. Understanding how children think and learn has proven useful for improving education.

- Describe theories relating to cognitive processing, learning, and memory

- Define how language and communication develop in pre-school children

- Identify stages of how drawings develop.

References

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (2010) Applied Human Development. https://www.cyccb.org/competencies/applied-human-development

CDC. (2023). Language milestones. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html

Child Mind Institute. (2024). What is neurodiversity? https://childmind.org/article/what-is-neurodiversity/

Government of Canada. (2018). Autism prevalence among children and youth in Canada: Report of the national autism spectrum disorder (ASD) surveillance system. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/infographic-autism-spectrum-disorder-children-youth-canada-2018.html

HealthLink BC. (2025). Preschooler Growth and Development. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/pregnancy-parenting/parenting-preschoolers-3-5-years/preschooler-growth-and-development

Indigenous Storybooks. (n.d.). Indigenous Storybooks resources. https://indigenousstorybooks.ca/about/resources/

Johnson, S. B., Blum, R. W., & Giedd, J. N. (2009). Adolescent maturity and the brain: the promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 45(3), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.016

Lally, M. & Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan development: A psychological perspective (2nd ed.). http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf

Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario. (2015). What are LDs? https://www.ldao.ca/introduction-to-ldsadhd/what-are-lds/

Leon, A. (n.d.). Children’s development: Prenatal through adolescent development. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1k1xtrXy6j9_NAqZdGv8nBn_I6-lDtEgEFf7skHjvE-Y/edit

Lumen Learning. (2019). Lifespan Development. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-lifespandevelopment/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). Excerpts from “ELECT”. https://www.dufferincounty.ca/sites/default/files/rtb/Excerpts-from-Early-Learning-for-Every-Child-Today.pdf

Pathways.org. (2023). Sensory integration. https://pathways.org/topics-of-development/sensory/

Paris, J., Ricardo, A., Rymond, A., & Johnson, A. (2021). Child Growth and Development. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Early_Childhood_Education/Book%3A_Child_Growth_and_Development_(Paris_Ricardo_Rymond_and_Johnson)

Pye, T., Scoffin, S., Quade, J., & Krieg, J. (2022). Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/childgrowthanddevelopment/

Seifert, K., & Sutton, R. (2009). Educational Psychology. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/educational-psychology

Siegler, R. (2024). Cognitive Development in Childhood. http://noba.to/8uv4fn9h

Wise, S. J. (2019). Neurodiversity terms. https://www.livedexperienceeducator.com/resources

OER Attributions:

Content from this reading has been adapted from the following sources:

Children’s Development: Prenatal through Adolescent Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, except where otherwise

Child Growth and Development Canadian Ed Copyright © 2022 by Tanya Pye; Susan Scoffin; Janice Quade; and Jane Krieg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Growth and Development by Paris, Ricardo, Rymond, and Johnson is shared under a CC BY license, except where otherwise noted.

Cognitive Development in Childhood by Robert Siegler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

“Educational Psychology” by Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton is licensed under a CC BY 3.0 International License.

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Lifespan Development – A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license, except where otherwise noted.