Child and Youth Care: Applied Human Development

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Investigate the domain of practice of Applied Human Development

- Identify areas of cultural diversity within child development

- Explore relevant social determinants of health as they apply to development

From last week:

- Describe the different forms of attachment

- Define Ecological Systems Theory

Introduction

Within the field of Child and Youth Care (CYC), there is a lot of information that we must consider – understand context – in order to best support healthy development for children and youth. Last week we began an overview of the main theories, concepts, and perspectives of child development we’ll cover throughout our course. This week’s reading explores cultural diversity, social determinants of health, and how our field views development. Regardless of the setting we are working in, development is a main focus. It provides benchmarks that we can compare and contrast a young person’s strengths, developments, and potentials for growth, relationships, and connection. Children do not grow in a vacuum. Their environment, the people around them, their communities, everything influences development.

Understanding the patterns of development provide the ability for professionals such as Child and Youth Care Practitioners (CYCPs) build caring and responsive relationships (OACYC, 2024), design safe and accessible environments which support children’s play and learning, both of which contribute to a sense of belonging and overall well-being (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014).

“It is almost redundant to point out that child and youth care workers have to be versed in human developmental knowledge, while observing and assessing and actually being engaged in work with the youngsters, ready to amass a vast repertoire of techniques, applied as these situations demand on the basis of on the-spot assessment. Such competencies, for the most part, have to be acquired in prior training where knowledge and application of knowledge is fused. Practice skills have to be initially learned within the context of simulated skill-building practice experiences and afterwards instep-by-step, well-selected and supervised actual practice experience in order to avoid that children or youth become the “guinea pigs” of the workers-in-training”

(Maier, 2009 p. 1).

Maier described that one of the most important aspects to learning for CYC Practitioners, is understanding development.

The third domain of practice for Child and Youth Care Practitioners (ACYCP, 2010) is ‘Applied Human Development.’

Chapter three in your textbook for Foundations in CYC also covers this domain of practice. Read on!

Applied Human Development

Professional practitioners promote the optimal development of children, youth, and their families in a variety of settings. The developmental-ecological perspective emphasizes the interaction between persons and their physical and social environments, including cultural and political settings. Special attention is given to the everyday lives of children and youth, including those at risk and with special needs, within the family, neighborhood, school and larger social-cultural context. Professional practitioners integrate current knowledge of human development with the skills, expertise, objectivity and self awareness essential for developing, implementing and evaluating effective programs and services.

A. Foundational Knowledge

The professional practitioner is well versed in current research and theory in human development with an emphasis on a developmental-ecological perspective.

- Lifespan human development

- Child and adolescent development as appropriate for the arena of practice, (including domains of cognitive, social-emotional, physiological, psycho-sexual, and spiritual development)

- Exceptionality in development (including at-risk and special needs circumstances such as trauma, child abuse/neglect, developmental psychopathology, and developmental disorders)

- Family development, systems and dynamics

B. Professional Competencies

- Contextual-Developmental Assessment

- assess different domains of development across various contexts

- evaluate the developmental appropriateness of environments with regard to the individual needs of clients

- assess client and family needs in relation to community opportunities, resources, and supports

- Sensitivity to Contextual Development in Relationships and Communication

- adjust for the effects of age, culture, background, experience, and developmental status on verbal and non-verbal communication

- communicate with the client in a manner which is developmentally sensitive and that reflects the clients’ developmental strengths and needs

- recognize the influence of the child/youth’s relationship history on the development of current relationships

- employ displays of affection and physical contact that reflect sensitivity for individuality, age, development, cultural and human diversity as well as consideration of laws, regulations, policies, and risks

- respond to behavior while encouraging and promoting several alternatives for the healthy expression of needs and feelings

- give accurate developmental information in a manner that facilitates growth

- partner with family in goal setting and designing developmental supports and interventions

- assist clients (to a level consistent with their development, abilities and receptiveness) to access relevant information about legislation/regulations, policies/standards, as well as additional supports and services

- Practice Methods that are Sensitive to Development and Context

- support development in a broad range of circumstances in different domains and contexts

- design and implement programs and planned environments including activities of daily living, which integrate developmental, preventive, and/or therapeutic objectives into the life space through the use of developmentally sensitive methodologies and techniques

- individualize plans to reflect differences in culture/human diversity, background, temperament, personality and differential rates of development across the domains of human development

- design and implement group work, counseling, and behavioral guidance, with sensitivity to the client’s individuality, age, development, and culture

- employ developmentally sensitive expectations in setting appropriate boundaries and limits

- create and maintain a safe and growth promoting environment

- make risk management decisions that reflect sensitivity for individuality, age, development, culture and human diversity, while also ensuring a safe and growth promoting environment

- Access Resources That Support Healthy Development

- locate and critically evaluate resources which support healthy development

- empower clients, and programs in gaining resources which support healthy development

The way this domain is organized, you can see how there is so much interconnectedness in our work. The more information we have, the better we can start where a young person is. To be a strong CYC Practitioner, we need to understand development across the lifespan, different contexts that are present, the environment, community, relationships, and how everything works together. This course, along with the rest of your courses throughout the program, will reinforce these concepts. Maier stated that “work with children or youth requires an intense interpersonal involvement at whatever level of development a child or youth is operating” (2009 p. 1) and this is a good summary of how we integrate our learning.

In the next section, we explore attachment, which is one of the theories that inform our work as CYCPs.

Attachment

Attachment is the close bond with a caregiver from which the infant derives a sense of security. The formation of attachments in infancy has been the subject of considerable research as attachments have been viewed as foundations for future relationships. Additionally, attachments form the basis for confidence and curiosity as toddlers, and as important influences on self-concept.

Figure 1.1: The formation of an attachment relationship (Photo by Marcin Jozwiak on Unsplash)

Harlow’s Research

In one classic study, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow investigated the responses of young rhesus monkeys to explore if breastfeeding was the most important factor to attachment.

Figure 1.2: Rhesus monkey sucking its thumb. (Image by splotter_nl is licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Infant monkeys were separated from their biological mothers, and two inanimate surrogate mothers were introduced to their cages. The first inanimate surrogate (the wire mother) consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second Inanimate surrogate was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terry-cloth blanket. The infant monkeys went to the wire “mother” for food, but they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm terry-cloth “mother.” The warm terry-cloth “mother” provided no food but did provide comfort (Harlow, 1958, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). The infant’s need for physical closeness and touching is referred to as contact comfort. Contact comfort is believed to be the foundation for attachment. The Harlows’ studies confirmed that babies have social as well as physical needs. Both monkeys and human babies need a secure base that allows them to feel safe. From this base, they can gain the confidence they need to venture out and explore their worlds.

Bowlby’s Theory

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond or tie that an infant forms with the mother. An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver in order to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1982, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as the child explores the surroundings.

Figure 1.3: A mother offering a secure base as her infant plays on a slide. (Image is licensed under CC0)

Bowlby said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment; the caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs; and the caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions (Bowlby, 1969, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). Additionally, Bowlby observed that infants would go to extraordinary lengths to prevent separation from their parents, such as crying, refusing to be comforted, and waiting for the caregiver to return.

Figure 1.4: This child is seeking comfort from an attachment figure. (Image on Pexels)

Bowlby also observed that these same expressions were common to many other mammals, and consequently argued that these negative responses to separation serve an evolutionary function. Because mammalian infants cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of adults for survival. Thus, those infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure were more likely to survive and reproduce.

Attachment Relationships in Indigenous Families

Parenting styles in Canada’s Indigenous cultures, First Nations, Metis and Inuit, are similar in some ways and differ in other ways. Values held in common include: a holistic approach to development, balance and respect. The Western view of the caregiver-child attachment relationship tends to focus on the child’s primary caregiver. In Indigenous cultures, a child is connected to his/her immediate family, extended family, community, and ancestors. All of these relationships are seen to be equally important.

The residential school system and the child protection system in Canada have had a profound and long-lasting effect on Indigenous people. Children who were removed from their families and raised in foster care or a residential school have become parents and grandparents. As children, they were subject to abuse, loss and trauma. As a result of this trauma, they are more likely to have difficulty forming healthy attachments as adults (Hardy & Bellamy, 2013).

Mary Ainsworth and the Strange Situation

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, continued studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth and her colleagues created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. The test is called The Strange Situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent (Ainsworth, 1979, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

Figure 1.5: An infant crawling on the floor with toys around as done in the Strange Situation. (Image is in the public domain)

During the procedure, which last about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, and then the parent again enters and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviours. Which are later coded by the research team. The investigators were especially interested in how the child responded to the caregiver leaving and returning to the room, referred to the “reunion”. On the basis of their behaviours, the children are categorized into one of four groups where each group reflect a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. One style is secure and the other three styles are referred to as insecure.

- A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the caregiver is present and may engage with the stranger. The child will typically play with the toys and bring one to the caregiver to show and describe from time to time. The child may be upset when the caregiver departs, but is also happy to see the caregiver return.

- A child with an ambivalent (sometimes called resistant) attachment style is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the caregiver rather than exploring the toys. When the caregiver leaves, the child is extremely distress and is ambivalent when the caregiver returns. The child may rush to the caregiver, but then fails to be comforted when picked up. The child may still be angry and even resist attempts to be soothed.

- A child with an avoidant attachment style will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother.

- A child with a disorganized/disoriented attachment style seems to have an inconsistent way coping with the stress of the strange situation. The child may cry during the separation, but avoid the mother when she returns. Or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor.

How common are the attachment styles among children? In Canada, attachment disorders are uncommon in the general population (under 1%). That increases to possibly 40% for children who are exposed to gross maltreatment or poor quality institutionalization (Atkinson & Beiser, 2016).

Cultural Diversity

There are many individual experiences that can influence development. Culture plays a big role in what makes us unique. Our own experiences, upbringing, culture, religion, etc. comes together to create a unique experience and can influence the relevance of developmental expectations or benchmarks. One area of a child’s development may emerge before another, which can be slightly outside of expected milestone achievements. This doesn’t mean that something is wrong, but instead means we must explore the context before making any decisions in terms of supporting healthy development.

The term culture refers to all of the beliefs, customs, ideas, behaviours, and traditions of a particular society that are passed through generations. Culture is transmitted to people through language as well as through the modeling of behaviour, and it defines which traits and behaviours are considered important, desirable, or undesirable.

Consider how our worldview affects the way we perceive the world. Every single one of our past experiences influences our worldview, and therefore the meaning we give to our experiences.

Our involvement in cultures plays a big part in creating the way we see the world. Both the way we assess a situation and how we approach decision making are filtered through our cultural lens (or lenses). We notice these lenses especially when we travel to a new area. We might find ourselves feeling confused by a new culture. We might find the experience of being in a new culture to be odd, interesting, or just plain different. We might feel invigorated, uncomfortable, or even frightened by the differences in culture.

When we find ourselves exposed to new situations and experiences like this, we face uncertainty. Humans really like to avoid the discomfort of uncertainty, so we – without even being aware of it – seek certainty. When we don’t know something, our brain goes to fill in the blank with something we do know–and that something will come from our own cultural lens! This can be detrimental when it comes to development, as our understanding of milestones may be skewed.

Our lens is simply what we know or consider to be “normal.” So it is understandable that we can have a really hard time becoming aware of our cultural lens. It feels much easier to just rely on what we already know and believe to be true for us. This is why it can become so easy to make assumptions and judgements about people from other cultures, a child’s stage of development, and how to best support this development. When we work and practice in our usual environments, with our usual community, we most often forget that we even have a cultural lens that’s always at work.

The goal of cultural humility is to become aware of our cultural lens and choose to let go of our biases so that we can perceive other cultures with respect and a sense of humility.

“Our cultural lens is so much a part of us that we are not even aware of how obvious it is to others. Like the nose on your face, you may forget that it is there, but everyone else sees it. I can’t look at you and not see your nose.” ~Susan C. Young (as cited Cusick, 2022).

Cultural Variations with Attachment

Some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2010, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021). For example, German parents value independence and Japanese mothers are typically by their children’s sides. As a result, the rate of insecure-avoidant attachments is higher in Germany and insecure-resistant attachments are higher in Japan. These differences reflect cultural variation rather than true insecurity (Van Ijzendoorn and Sagi, 1999, as cited in Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson, 2021).

A research study of development among Indigenous children in Canada, conducted by Findlay, Kohen and Miller (2014), concluded that the age range for the development of certain skills, including social skills, can be different for Indigenous children compared to the general population. For example, the cultural norm in some Indigenous identity groups of living with extended family members may influence the development of certain social skills by providing additional support and modelling behaviour. The study also found variations between Indigenous identity groups (Metis, Inuit and off-reserve First Nations) in expectations for children to develop independent behaviours. The researchers emphasized the importance of using culturally specific age ranges and interventions because using those based on the general population might result in over or under identification of children at risk for developmental delays. (Findlay, Kohen, & Miller, 2014).

Exploring our next topic, the Social Determinants of Health, we will further explore how culture further ties in to our understanding of development.

Social Determinants of Health

In the past, a child’s development was often determined by how they met various milestones laid out by individuals who created theories, perspectives, and guidelines that were followed for decades. As research continued, other theories and a varied understanding emerged.

Since the 1970s, Canada has gone beyond theories and perspectives, and using decades of research conducted within Canada and worldwide, the concept of the social determinants of health was developed. These determinants outline that some of the factors that shape our health include our living and working conditions, how income and wealth is distributed, services we receive (e.g., health and social services), and access to employment, education, food and housing security, among other factors (Raphael, Bryant, Mikkonen & Raphael, 2020).

Below is a list and a brief description of the Government of Canada’s (2023) list of the social determinants of health.

As you go through the list, think about how these areas may impact a child’s development and access to services. Remember to take notes!

1. Income and Social Status

The higher a person’s income and social status, the better their health will be.

The article Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts, (Mikkonen and Raphael, 2010. Pg. 12) states the following about income:

Income is perhaps the most important social determinant of health. Level of income shapes overall living conditions, affects psychological functioning, and influences health-related behaviours such as quality of diet, extent of physical activity, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol use. In Canada, income determines the quality of other social determinants of health such as food security, housing, and other basic prerequisites of health. (2010)

Have you noticed this connection to income, social status and health in your life, or the lives of people close to you? How did it make you feel?

2. Employment and Working Conditions

People who are unemployed or underemployed are less likely to experience consistently good health. Also, those who work in environments that are unsafe have additional barriers to health. These situations affect us both mentally and physically.

Also from the article Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts, (Mikkonen and Raphael, 2010. Pg. 17):

Employment provides income, a sense of identity and helps to structure day-to-day life. Unemployment frequently leads to material and social deprivation, psychological stress, and the adoption of health-threatening coping behaviours. Lack of employment is associated with physical and mental health problems that include depression, anxiety and increased suicide rates. (2010)

3. Education and Literacy

People who have a higher socioeconomic status are more likely to have post-secondary educational opportunities, and be able to earn degrees and certifications, which increases their determinants of health.

The Government of Canada website article Social and Economic Factors that Influence Our Health and Contribute to Health Inequalities states the following about education:

Generally, being well-educated equates to a better job, higher income, greater health literacy, a wider understanding of the implications of unhealthy behaviour and an increased ability to navigate the healthcare system – all of which lead to better health. The data in Chapter 3 indicate that Canadians with lower levels of education often experience poorer health outcomes, including reduced life expectancy and higher rates of infant mortality. (n.d.)

4. Childhood Experiences

Childhood development sets people on a path towards good health or poor health, enhanced or decreased well-being. Consider the Adverse Childhood Experiences study conducted by the US Center for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente. The study surveyed 17,000 people and found that those who have adverse childhood experiences are at a greater risk for health issues in adulthood. (It’s important to note that of the 17,000 people studied, 100% had jobs and health insurance, 74.8% were white, 75.2% had attended some college, or had a degree. The study focused on families of origin and didn’t track adverse experiences caused by systems.)

Within this context, we must understand and acknowledge that experiences of intergenerational trauma, discrimination and other factors are important social determinants of health.

What are some ways our childhood experience affect us as adults?

5. Physical Environments

Exposure to unsafe levels of contaminants through water, food, air and soil can negatively affect health. Housing, transportation and access to resources also have a huge impact on health.

Many studies show that unsafe or poor quality housing, homelessness and food insecurity all have direct impacts on our health. We know that some Canadian homes, especially on Indigenous reserves, lack clean water and basic sanitation – and many are overcrowded.

Overcrowding and a lack of clean water or sanitation can lead to the spread of illness and disease. Living in inadequate housing can also increase stress and impact people’s ways of coping, including substance use. We also know that those who are experiencing homelessness have a much higher rate of a wide range of physical health problems and mental health diagnoses than the general population.

The report Key Health Inequalities in Canada: A National Portrait (Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, 2018, Pg. 341 & 342) states:

Poor housing conditions, including issues such as mold, overcrowding, and lack of affordability, have been associated with a wide range of health conditions such as respiratory and other infectious diseases, chronic diseases (e.g. asthma), injuries, inadequate nutrition, adverse childhood development, and poor mental health outcomes… The prevalence of housing below standards among Indigenous peoples in Canada was higher than among non-Indigenous people. First Nations people living off reserve had prevalence of housing below standards 1.5 (95% CI: 1.5–1.6) times that of non-Indigenous people.

What do you think are the drivers that lead someone to live in poor conditions?

What circumstances could be beyond their control that end up affecting their living conditions?

Do you think there are enough services to support people who live in inadequate housing conditions?

6. Social Supports and Coping Skills

High levels of support from family, friends, and communities are associated with better health outcomes. Community and belonging are recognized as being important determinants of health. When people have communities that are stable, diverse, safe, and cohesive, one’s overall health is enhanced.

Practices that support disease prevention and promote self-care, including coping with adversity and developing self-reliance, all support people’s overall health. However, it is important to recognize that personal life “choices” are hugely influenced by the socioeconomic environment; some people do not have options for engaging in these practices.

Do you feel like you have a strong support system? If so, how do they support you?

If not, is there anyone in your life right now who you’d like to work on building a stronger relationship with? What will you do to build that connection?

7. Healthy Behaviours

Our behaviours greatly affect our health. The resources available to us impact our access to options and will be drastically different for everyone. Some people who are negatively affected by many of the social determinants of health will have less resources available to them. This affects everything from food choices to leisure and activity options.

From the article Social Determinants and Health Behaviors: Conceptual Frames and Empirical Advances (Short & Mollborn, 2016):

Health behaviors, sometimes called health-related behaviors, are actions taken by individuals that affect health or mortality. These actions may be intentional or unintentional, and can promote or detract from the health of the actor or others. Actions that can be classified as health behaviors are many; examples include smoking, substance use, diet, physical activity, sleep, risky sexual activities, health care seeking behaviors, and adherence to prescribed medical treatments. Health behaviors are frequently discussed as individual-level behaviors, but they can be measured and summarized for individuals, groups, or populations. Health behaviors are dynamic, varying over the lifespan, across cohorts, across settings, and over time. (2016)

8. Access to Health Services

Those who have access to health care services and have the funds to pay for services that are not free, will be healthier than those who can’t access services.

Though we have universal healthcare in Canada, there are still disparities as many services, such as eyecare, dental care, some pharmaceuticals, and access to alternative health practitioners, are not covered.

For example, diabetes is a disease that comes with a high price tag for ongoing care. Medications, pumps, and test strips are very expensive. People who can’t afford these medications and supplies will tend not to keep tight control of their blood sugars, which can have a serious impact on their physical and mental health.

Have you ever been in a position where you haven’t been able to access healthcare services? If so, how did that feel?

9. Biology and Genetic Endowment

Genetic endowment can predispose people to particular diseases or health problems.

The HealthyPeople.gov website article Determinants of Health (n.d.) states,

Some biological and genetic factors affect specific populations more than others. For example, older adults are biologically prone to being in poorer health than adolescents due to the physical and cognitive effects of aging.

Sickle cell disease is a common example of a genetic determinant of health. Sickle cell is a condition that people inherit when both parents carry the gene for sickle cell. The gene is most common in people with ancestors from West African countries, Mediterranean countries, South or Central American countries, Caribbean islands, India, and Saudi Arabia.

10. Gender

Society tends to link different personality traits, attitudes, behaviours, values, and levels of power and influence to gender. These societal norms have a big impact on one’s health in the way the health care system offers treatment.

From Chapter 2 of The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2012 – Sex, gender and public health:

Socio-economic factors can contribute to inequalities in health outcomes not only between women and men, but among and between different groups of women and men. These factors can influence opportunities for good health and well-being

Consider gender outside of the binary confines of male and female. Life can be increasingly complex for those who are outside of traditional Western gender norms. Discrimination and prejudice are major issues that affect one’s overall health for those who are Two-Spirit, transgender, and non-binary.

Have you ever noticed your own gender affecting your health outcomes? Why or why not?

11. Culture

People who identify with cultures outside of the dominant culture of Canada can feel marginalized. They often face stigmatization and are not able to receive culturally appropriate services. This important topic is covered extensively in the Cultural Humility module.

In the Canadian Public Health Association article, Racism and Public Health (2018):

Canada remains a nation where a person’s colour, religion, culture or ethnic origin* are determinants of health that result in inequities in social inclusion, economic outcomes, personal health, and access to and quality of health and social services. These effects are especially evident for racialized and Indigenous peoples as well as those at the lower end of the social gradient and those who are incarcerated (populations that are also disproportionately composed of racialized and Indigenous people). Complicating this scenario are government and non-governmental systems that impose barriers on those in need which limits their ability to obtain the services and benefits that are easily available to most Canadians. Steps must be taken to eliminate these systemic barriers. (2018)

What do you think is missing from the list above?

Now take some time to consider the following:

- Indigenous culture, and Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- Disability and the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- Food Insecurity

- Homelessness

- Substance use issues

Decolonization: Since Canada’s dominant society reflects a Eurocentric attitude, it is essential that we dig deeper into these SDOH to understand and decrease discrimination. As you consider these social determinants, notice how colonization continues to inform every area of society and how we might work to make change.

All of the areas highlighted by this list directly (or indirectly) influence a child’s development. As we go through the course, we will revisit how we as CYCPs can support with these areas when supporting a child or youth with healthy development.

This section has been adapted from: Post-Secondary Peer Support Training Curriculum by Jenn Cusick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Ecological Systems Theory

“Ecological theory, in particular the pioneering work of Urie Bronfenbrenner, has been influential in the field of Child and Youth Care. Ecological theory not only has deep and far-reaching roots in the field, but also has the potential to influence new directions and development in Child and Youth Care”

(Derksen, 2010 p. 326).

As CYCPs, having an overall understanding of important theories such as Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory, knowing a child’s environment, focusing on relationships (including attachment) allow us to provide a wrap-around approach to supporting healthy development. Our Scope of Practice, as described by the Ontario Association of Child and Youth Care (OACYC, 2021).

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development. Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

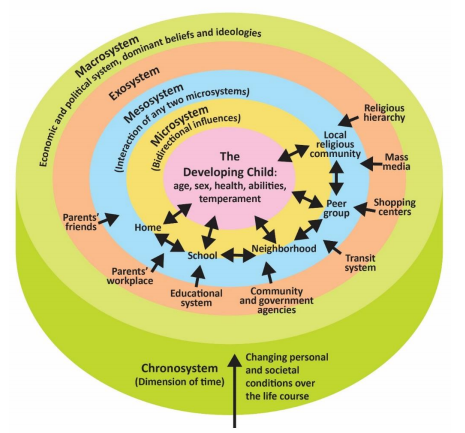

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development.

Table 1.6 Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

| Name of the System | Description of System |

| Microsystems | Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them need to be considered. For example, to appreciate what is going on with a student in math, the relationship between the student and teacher should be known. |

| Mesosystems | Mesosystems are interactions between those surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example, will indirectly affect the child. |

| Exosystem | Larger institutions such as the mass media or the healthcare system are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families and peers and schools that operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions. |

| Macrosystems | We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual. |

| Chronosystem | All of this happens in a historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies of educational institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time. |

Indigenous Perspectives

As for Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, it seems the same as the saying: It takes a community to raise a child. In some Indigenous communities, the aunts and uncles are the ones who “discipline” children to keep harmony in the family. Discipline in the sense that they talk to the children when they are not contributing to the household or when they are giving their parents a hard time. It is common for children to go live with either aunts and uncles, or grandparents for periods of time to learn different skills, knowledge and/or teachings as well as to go help out with child-rearing. There is a strong sense of sharing our gifts from the Creator, the children, with our extended family. They are considered to be lent to us by the Creator.

Summary

In this chapter we looked at:

- Investigate the domain of practice of Applied Human Development

- Identify areas of cultural diversity within child development

- Explore relevant social determinants of health as they apply to development

From last week:

- Describe the different forms of attachment

- Define Ecological Systems Theory

References

Association for Child and Youth Care Practice. (2010) Applied Human Development. Retrieved from: https://www.cyccb.org/competencies/applied-human-development

Atkinson, L. & Beiser, M. (Eds.). (2016). Attachment disorders. In caring for kids new to Canada. Retrieved from https://kidsnewtocanada.ca/mental-health/attachment-disorders

Canada, P. H. A. of. (2012, October 26). Sex, gender and public health. The Chief Public Health Officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada 2012 – Influencing health – the importance of sex and gender. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/chief-public-health-officer-report-on-state-public-health-canada-2012/chapter-2.html.

Cusick, J. (2022). Foundations of support: A peer perspective. Alberta Health Services, Mental Health Recovery Partners.

Derksen, T. (2010). The Influence of Ecological Theory in Child and Youth Care: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 1(3/4), 326-339. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs13/420102091

Findlay, L., Kohen, D., & Miller, A. (2014). Developmental milestones among Aboriginal children in Canada. Paediatrics & child health, 19(5), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/19.5.241).

Government of Canada. (2023). Social determinants of health and health inequalities. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html

Hardy, C. & Bellamy, S. (Eds). (2013). Caregiver-infant attachement for aborigional families. Retrieved from https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/health/FS-InfantAttachment-Hardy-Bellamy-EN.pdf

Maier, H. W. (2009). A Developmental Perspective for Child and Youth Care Work. Journal of Child and Youth Care, Vol.8 No.2, pp. 57-70.

Mikkonen, J. & Raphael, D. (2010). Social determinants of health the Canadian facts. York University School of Health Policy and Management.Toronto, Ontario.

OACYC. (2021). Scope of Practice. Retrieved from https://oacyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/OACYC-Scope-of-Practice-2021.11.20.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2014). How does learning happen? Ontario’s pedagogy for the early years: A resource about learning through relationships for those who work with young children and their families. Retrieved from https://files.ontario.ca/edu-how-does-learning-happen-en-2021-03-23.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada and the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative. (2018).Key health inequalities in Canada: A national portrait. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/science-research/key-health-inequalities-canada-national-portrait-executive-summary/key_health_inequalities_full_report-eng.pdf

Raphael, D., Bryant, T., Mikkonen, J. and Raphael, A. (2020). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts. (2nd ed.) Oshawa: Ontario Tech University Faculty of Health Sciences and Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management.

Short, S. E., & Mollborn, S. (2015). Social determinants and health behaviors: Conceptual frames and empirical advances. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.002

OER Attributions:

Children’s Development: Prenatal through Adolescent Development by Anna R. Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Post-Secondary Peer Support Training Curriculum by Jenn Cusick is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Child, Family, and Community by College of the Canyons, Rebecca Laff, and Wendy Ruiz is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 international license.