16 Elicitation Techniques

Introduction

Elicitation Techniques

Elicitation is a term that describes techniques which enable teachers to get learners to provide information that they already know by activating their prior experiences and knowledge gained from course reading and discussions, rather than telling them. When learners can link new knowledge to something they already know, they are more likely to remember it long term. Elicitation is at the heart of student-centred learning.

Expand Your Knowledge

Expand Your Knowledge

Using elicitation techniques can be an effective diagnostic tool for the teacher because it helps to expose what learners already do or do not know and helps teachers make decisions about what content areas need more or less focus. Learners have more agency in their learning and can self-identify the gaps between what they know and what they need to know. There are several elicitation techniques that teachers can incorporate effectively into classes to engage learners.

Using Pictures and Guided Questions

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Carefully chosen pictures that clearly target a concept are effective for ELLs because they are not language dependent. Learners can connect the picture to their prior experience so they do not have to struggle with decoding the language first to determine the underlying concepts. Pictures let ELLs quickly understand the concept and free up processing time to focus on how to express what they know about the subject.

Look at the pictures in this collage and determine what they could elicit from the students if presented in class as part of the lesson.

Using Actions and Guided Questions

Role plays, videos and demonstrations help students make connections to the course content.

List three activities that you could connect to the following demonstration to support mastery of course content.

Asking Better Questions

Following is an excerpt from “The Creative Teaching and Learning Resource Book” by B. Best and W. Thomas.

Asking better questions

Study the prompt questions and use them as a resource with students. Do not be too impatient for quick answers after asking questions – give plenty of ‘wait time’ and encourage students not to say the first thing that comes into their heads.

Prompt questions

The key to effective questioning is to ask as many open questions as possible – i.e. those that do not allow students to answer in ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. The following questions provide examples you might use in classroom contexts.

Click on the question type categories to see suggested questions to elicit student participation.

Source:

Best, Brin, and Will Thomas. The Creative Teaching and Learning Resource Book, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/senecac/detail.action?docID=601600.

Make Connections

Make Connections

Locate one video or describe one demonstration or roleplay that you could use to help students meet the learning outcomes of your course.

Using Charts and Graphic Organizers

KWL Charts can be used to elicit what students already know, what they want to know and what they have learned by the end of the lesson – it is a helpful tool to gauge student learning. Use of graphic organizers like VENN diagrams can be used to have students illustrate their understanding of one concept in relation to another.

Questioning Techniques

Our final comparison involves the role of teachers. In traditional classrooms, teachers generally behave in a didactic manner, disseminating information to learners. In constructivist classrooms, teachers generally behave in an interactive manner, mediating the environment for students. Constructivist instructors engage learners to participate actively using interesting questions, problems, and materials.

Traditional didactic teachers disseminate information to learners. If they do pose questions to students in class, it is generally to check basic understanding of course information. In constructivist classes, teachers use questioning techniques to help students build knowledge collaboratively. Skillful use of questions supports student-centred learning. Depending on the type of questions posed, learners can either become actively engaged or they can interact with the course learning activities at a superficial level. Through effective use of questions, teachers create a learning experience that invites authentic reflection and discussion.

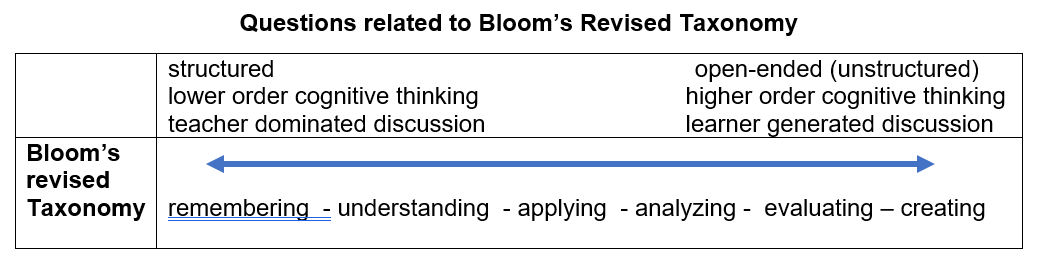

Structured vs. Open-Ended Questions

Structured questions are close-ended questions designed by the instructor to elicit specific responses. Generally they require low cognitive load to respond to and may be easier to answer as they generally require regurgitation of factual information rather than personal opinion. Open-ended questions do not have an expected response and consequently have a higher cognitive load. Reponses are not predetermined and are based on learners’ experiences, feelings and understanding.

Convergent vs. Divergent Questions

Questions can be convergent or divergent. Convergent questions are typically factual with one or limited acceptable answers. An example of a convergent question is “What is the capital of Canada?” There is only one correct answer and this question just requires recall. Leaners may be reluctant to respond because they fear making a mistake. Furthermore, the responses will end as soon as the “target” answer sought by the teacher is given. A convergent question, on the other hand, encourages a variety of responses that are not necessarily predetermined. There can be a number of ‘correct’ responses and convergent questions are likely to generate discussion. An example of a convergent question is “What is the difference between “all natural” and “organic”?

Lower Level vs Higher Level Cognitive Questions

Lower level questions draw on memorization, comprehension, or application. There is usually only one correct answer or a pre-determined narrow range of acceptable answers. Lower level questions generally require a few words or very brief responses. In contrast, higher level questions require more cognitive engagement. These questions that require analysis, synthesis, or evaluation, are more likely to generate extended discussions. Higher level questions encourage students to examine the question from multiple perspectives as there is no one right answer.

Divergent, higher order question types generate more meaningful interaction than convergent lower order question types. Questions should elicit and build on pre-existing understandings that students bring

with them and tie in directly to the key concepts the students are learning. Questions should be relevant and connected to the learning outcomes.

Watch & Share

Watch & Share

Watch the video to learn how other professors use questions to engage students in their learning.

Apply

Apply

Look at the chart with the types of questions on the continuum of Bloom’s revised technology. Click on question types to see question prompts that will elicit specific types of responses.

Select one lesson in your course and create a question from at least 3 categories that could be used in your course. The question prompts are from the Academy of Art University, Faculty Evaluation and Training Department.

Tips for eliciting engagement in learner centred classes

- You do not need to elicit every detail from students; use elicitation techniques in meaningful contexts.

- Be mindful that many of your ELLs may not be used to voicing their individual opinions or sharing knowledge. They may be more comfortable in classes where the professor provides all content information. Set ELLs up for success.

- In collectivist cultures students do not want to stand out in the class either by a great performance or as a negative one.

- Clearly articulate that type of behaviour and participation that you expect in the classroom.

- Start by asking your ELLs questions you are confident they know the answer to which will help them develop confidence in sharing their ideas with others.

- Higher-level thinking questions that require application, analysis, evaluation and creation, are cognitively more challenging and take time and effort to respond to coherently.

- Critical thinking is valued in North American Education. Elicitation questions help ELLs discover their voice, and be acknowledged for having a point of view.

- Wait time is important. All students benefit from time to process a posed question and to formulate a coherent response. Students do not want to lose face in front of their peers so they may be hesitant to risk an incorrect or incomplete response. For ELLs, more wait time is required. They are often translating the question into their native language, formulating a response in their native language based on their prior and current knowledge, and then translating that response into English. Finding the right words to express their thoughts can be challenging, in particular if they are put on the spot in front of the entire class.

- Gauge when wait time becomes excessive or students start answering mostly incorrectly – this is a good indication that they have shared their current level of understanding and are not able to make further connections.

- Consider the time you have available for the open questions.

- As you plan active learning activities such as debates, discussions, minute papers, and think-pair-share activities, strategize how you will insert key questions.

- prepare your questions in advance – keep in mind the key learning outcomes of your lesson and of the course – script the questions you will pose

- consider the purpose of your question – are you concept checking, trying to determine what they know already, trying to get them to make higher order connections?

- decide in advance if the question will be posed to one person, pairs, groups or the whole class

- carefully choose the level of difficulty of the question depending on the level of your students

- consider the wording of your questions – use vocabulary that is familiar to the students

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

- Effective questions are:

purposeful – asked to achieve a specific purpose

clear – students understand what they mean

brief – stated in as few words as possible

natural – stated simply, in conversational English

thought-provoking – they stimulate thought and response

limited in scope – only one or two points in chain of reasoning called for adapted to the level of the class – tailored to the kinds of students in the class (Lewis, 2007.)

Apply

Apply

- Find a recorded lecture in your subject areas.

- Determine how you would break it down into appropriate learning chunks.

- Script elicitation questions that you could use if you were to teach that lesson.