Geospatial Art-Creation in Multi-Sensory and Digital Worlds

Making sense beyond the visual

Creative geovisualization has opened up all kinds of possibilities for digital humanities research exploring the intersections of history, geography, and art. It is important to recognize, however, that places and spaces of the past, present, and future are sensed in all ways that go beyond the visual. Not discounting the evocative, descriptive, and connective potential of creative geovisualization, it is worth considering what might be “overlooked” in storytelling projects that focus so explicitly on the visual. What is the tactility or sonicity of a digital map? How does a placefeel differently when viewing it on a screen through a GIS interface? Such questions do not imply that digital representations of place are not textured, emotive, or multi-sensory; indeed, Gillian Rose’s work on interface, network, and friction suggest otherwise (2016). However, a more dedicated focus on the more-than-digital and more-than-visual might actually enhance creative geovisualization projects in the future.

For the remainder of the module, we consider the storymapping opportunities that are created through a greater attentiveness to the more-than-visual world and consider some of the methods used to communicate such relationships. These include tactile, hand arts practices of beadwork (“re-mapping” Lake Nipissing), and the affective dimensions of sound (e.g. making climate and hydrological data “sing” through digital data sonification). The examples below are also connected through the use of geospatial art-creation to explore the ongoing histories of environmental and climate change. All of them showcase the fluid, multi-sensory spatialities of the digital, material, human, and non-human, inspiring further questions like: what is art, what is data, what is the past, and what is space?

The Lake Nipissing Beading Project (2020-)

Authors’ Note: The authors of this module are settler-geographers who were involved as part of the Lake Nipissing Beading Project organizing team. We use first-person language at times to situate ourselves in the narrative when appropriate, but we acknowledge that we are only part of a much larger collaboration that includes First Nation members, settlers, academics, and non-academics who all shape and interpret the project in different ways beyond what we are able to discuss briefly here. Please visit the website (listed at the top of the module) for a list of fellow team members, without whom this project and module would not be possible.

Content Warning: In the “Beading Active Histories” section, we mention the painful discovery of mass graves of children at sites of former residential schools across Canada as a factor shaping the project. Please take care while reading and feel welcome to skip ahead if needed.

Lake Nipissing (Nbisiing) is situated in the heart of Anishinaabeg territory and is part of the lands protected by the Robinson Huron Treaty. As mentioned in the introductory module, Nipissing University is located on these lands which have been stewarded by the Nbisiing Anishinaabeg for thousands of years. The lake is imbued with many different meanings, variably shaped by different cultural, historical, environmental, economic, and political contexts. However, like the rest of Canada, much of the “public record” about the region, and the lake, remains dominated by settler colonial histories and knowledges about place.

How is Lake Nipissing known, situated, and related (to)? What kinds of relationships to and with Lake Nipissing exist in dominant representations of the lake? What and who is missing from these dominant portrayals of place? What else might be known about the lake, and how?

These are some of the questions that guide the Lake Nipissing Beading Project, alongside broader objectives of decolonizing historical-geographical knowledges of place, honouring Indigenous-settler treaty relations, and “engaging in and establishing relationships through the act of creation and sharing” (Beaucage and Srigley, 2021).

The Lake Nipissing Beading Project is a 5-metre beaded reimagining of Lake Nipissing (Nbisiing) and its tributaries. The project is an ongoing, collaborative, and community-based effort that resulted in a traveling art installation, organized by bead artist Carrie Allison, in collaboration with Dokis First Nation, Nipissing First Nation, and Nipissing University Departments of History and Geography. The beaded “map” was created by joining 444 individually-beaded felt squares. Each square was sent to participants with bead kits (Fig.3) and an image indicating which part of the lake or surrounding waterways to bead. Members of Nipissing and Dokis First Nations, whose ancestral relationship to the lake stretches millennia, were also invited to select a specific part of the lake to bead to further imbue it with meaning.

Project Inspirations

The Lake Nipissing Beading Project (LNBP) is part of a larger place-based research partnership between Nipissing First Nation, Dokis First Nation, Nipissing University, and museums across Anishinaabeg and Robinson Huron Treaty territory. A key objective of this partnership involves using the group’s collective abilities to challenge the histories and knowledges produced through colonial institutions (like universities and museums), while re-centring Indigenous knowledges, practices, and worldviews about land and relationship.

Although the project is guided by a team of coordinators, it did not emerge from a single event or person; rather, it was a culmination of many factors coming together in various, often serendipitous ways. Some of these included: a collective desire to build connection and foster community during the isolation of a global pandemic; concern about colonial land encroachment and environmental degradation; ongoing research on the cultural and environmental histories of Nbisiing lands and relations, including Anishinaabeg beaders and knowledge keepers (McLeod Shabogesic, 2021); and responses to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action regarding decolonization, reconciliation, and education.

The beading project was imagined as a way to bring Nipissing and Dokis First Nations, among other people with connections to Lake Nipissing, together through a shared project that involved beading in relationship with the land and water, as well as each other. As project artist, Carrie Allison, explains:

We bead to show respect and acknowledge the importance of this waterway to those across this continent, we are all connected and the water shows us this. (Lake Nipissing Beading Project, 2021)

In beading treaty relations and using art-creation to “speak back” to colonial maps, the Lake Nipissing Beading Project drew inspiration from The Shubenacadie River Project led by Carrie Allison in 2018-2019. The Shubenacadie River Project was an art-action response in opposition to an Alton Gas proposal to create salt caverns for the storage of natural gas on Mi’kmaq lands that would release toxic waste into the river and was in direct violation of the Peace and Friendship Treaties governing the land (Stop Alton Gas, 2022). Allison developed an activist-community intervention that was “an exercise in beading treaty relations” and part of grassroots organizing to stop the project (Allison, 2019). The resulting forty-foot beaded “map” of the river was installed at the Treaty Space Gallery in Kjipuktuk (Halifax). On The Shubenacadie River Beading Project website, Allison explains that collaborative activities “foster storytelling, sharing, engagement, and collective making” which, she continues, is also a process of “activating Indigenous research methodologies.” In 2021, after eight years of opposition, the Alton Gas project was cancelled and will be decommissioned (CBC, 2021).

The LNBP was also preceded by a speaker series, hosted by Suzanne Campeau Whiteduck (Nipissing First Nation), that invited beadwork artists and scholars to speak about a variety of beading-related topics, including beading as relationship, cultural histories of beading, and beading as methodology in academic research, among others. We recommend (but do not require) viewing them to gain a broader sense of the themes pursued throughout the project, and to hear from lead artist, Carrie Allison, about the creative and action-oriented goals of the project (Fig. 4).

As two of the project co-ordinators, Glenna Beaucage (former Culture & Heritage Manager, Nipissing First Nation) and Katrina Srigley (History, Nipissing University), outlined in their presentation, “Beading through Nbisiing Nishnaabeg Histories,” beading is another meaningful way to honour histories of Lake Nipissing and its stewards:

“We understand the work we do together on the histories of the Nbisiing Anishnabek as a process of what we’ve called animating Nbisiing lands and waterways with stories.” (Beaucage and Srigley, 2021)

Although the project invites participation from non-Indigenous participants and organizers (including us), it is guided by Anishinaabeg research values of relational storytelling and story listening, working in relationship (“in a good way”), and land- and treaty-based knowledges (see, for example, Geniusz, 2009; Peltier et al., 2018; Simpson, 2014; Srigley, 2020). In this particular case, the project engages with these approaches through collaborative and geospatial art-creation, which ties together many different histories, geographies, politics, research trajectories, and community initiatives. More detailed information about project and artistic inspirations can be found in the online video that accompanied the Lake Nipissing Beading Project exhibit opening at the Treaty Space Gallery in Kjipuktuk (Halifax, Nova Scotia) in September 2021, as well as Speaker Series presentations, all of which are available on the project website. To better understand the geospatial aspects of the project, we now turn to a discussion of the various forms of “mapping” involved.

The “Basemap”

Given that the Lake Nipissing Beading Project occurred when participants could not gather together, and was designed to be collaborative, a key challenge was in determining the initial design. The project leaders decided to begin with a georeferenced “basemap” that could be organized as a grid of squares, each producing its own shapefile. This process, led by environmental geographer, Ysabel Castle (Nipissing University), allowed for hundreds of different squares to be beaded in separate locations before being joined back together. The map shared in digital form on the project website (see “The Beaded Map“) was produced through a multi-step process that involved receiving, photographing and numerically labeling each square based on its grid location, and then joined together with other tiles using a process called “mosaicking” to reassemble the lake. In the accompanying lab, you will be introduced to some of the methods used to locate and grid remote sensing images as one way of working with historical and geospatial data for digital art-creations.

Castle and the team used aerial photo imagery collected by the Ministry of Natural Resources in 2008-2009 as part of the Forest Resource Inventory, often used to determine tree species and vegetation health. Remote sensing uses different wavelengths of energy including red, green, and blue light, but also infrared, which interacts with water and vegetation differently than visible light. These wavelengths can be used in various combinations to study different phenomena, and each combination produces characteristic colours when printed or displayed on a computer screen. In one of the images, the lake had a deep green hue, which led to the artistic decision to use emerald green beads for the lake. In addition to being an aesthetic choice, the colour selection further disrupts the (often unquestioned) representations of land-as-green and water-as-blue in mapping.

As we discuss further in the module on counter-mapping, however, using colonial geospatial technologies like aerial photography, remote sensing, maps, and GIS, raises important questions about the extent to which the project can fulfill decolonial objectives. In the descriptive panel accompanying the art installation, project coordinators recognize the historical context of the relationship between geospatial techniques and colonial violence, highlighting the complexity of using colonial technologies (maps, remote sensing, GIS) while also subverting it through beadwork as an act of reclamation:

This map has been created by assigning coordinates to the corners of the tiles so they can be overlain on their real-world locations, using a GIS (short for Geographic Information System). GIS technology is used to create, analyze and display spatial data, and has largely replaced manual cartography techniques. A GIS is a powerful tool for map-making, and like any map making technology has great potential for both harm and benefit.

Map making has historically been used to disenfranchise and take land from Indigenous peoples across the globe. This project uses map making technology to take some of that power back by beading over it, with the beads standing in for Indigenous sovereignty. Water has always been a part of Indigenous territories and Indigenous ways of existing. In beading Lake Nipissing together, we honour the connective features of water, land and community. Water is life.

This acknowledgement of the colonial histories of the geospatial technologies used, and the subsequent disruption and subversion of them through beading non-colonial knowledges into the design, is an important part of the artistic process. In this case, the context of working collaboratively, but apart, led to the decision to begin with geospatial imagery that had already been created. However, the project might be better understood as an endeavour in “counter-mapping” (Hunt and Stevenson, 2017; Peluso, 1995), “remapping” (Goeman, 2013) or “unmapping” (Razack, 2002), as a means of denaturalizing settler cartographies and other colonial logics. We discuss these further in the Counter-mapping module, and consider the beaded map – in digital and material form – below as an example of re-mapping historical relationships with land and water as a process of reclamation and repair.

Material and digital re-mappings of Lake Nipissing

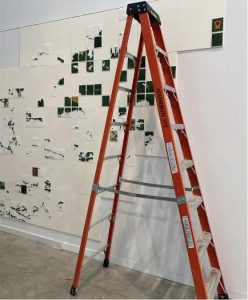

The resulting beaded map of Lake Nipissing might be better described in a plural form, given that the project has produced a material, tactile beaded map that was stitched and later adhered together to form a traveling art installation (Fig. 5), but was also shared as an interactive map online through the project website (Fig. 6).

The material, stitched, beaded map is a mobile – and mobilizing – piece of art. It is continually under construction, with new squares being added as they come in, and new meanings will be attached even once the squares have all been received. The installation is designed as a traveling exhibition, starting at the Treaty Space Gallery in Kjipuktuk (Halifax) to commemorate the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (also known as Orange Shirt Day), and then travelling back to Anishinaabeg territory where it will stop in several communities across Northern Ontario. Doing so allows more communities to experience and spend time with the map up close, acknowledging the relationships between beadwork, ancestral histories, and the importance of visitation spaces, as discussed by several beaders in the project’s speaker series (see Speaker Series III, for example). Finally, as project coordinators Srigley and Beaucage noted in their presentation (Speaker Series VI), beading, and the multiple forms of mapping involved, “animate” land and waterways, mobilizing dynamic cultural histories of place that re-centre Anishinaabe practices and strengthen relationships.

We mentioned earlier that the LNBP team used mosaicking techniques with georeferenced imagery to develop a basemap and organize it into a grid. Establishing an interactive, online presence for the project, and inviting new ways of relating to both the lake and the project, the map shown on the website incorporates the georeferenced grid and reintroduces creative geovisualization in a digital format (Fig. 6). These geovisual methods include taking and uploading high-resolution digital photographs of each beaded tile, along with creative GIS to geolocate each tile on the gridded basemap with attribute data. Users can zoom in on particular parts of the lake to see a high level of detail in the beaded and unbeaded parts, or zoom out to see the project in full, showing individual tiles stitched together as one evolving piece of art.

As the GIS evolves, a user might also be able to click on an individual tile to learn more about that particular location, including reading or hearing stories about that place from the person who beaded it and has consented to sharing their story. This kind of interactivity invites audience appreciation, not only the aesthetics and the histories on display, but also labour involved in both beading and creative geovisualization. Furthermore, the level of inter-textuality afforded by creative geovisualization opens up many more possibilities for connecting polyvocal (hi)stories, places, and relations.

The physical, beaded map and the online, digital map may be viewed on their own but they are perhaps most powerful when they are appreciated together. Each map shares and extends the space of the other. Both directly challenge colonial legacies of mapping and provide a space for reclamation of Indigenous knowledges and treaty-based relationships. Both invite respectful “witnessing” and “relating to” the lake and the project as they undergo dynamic change together.

Beading Active Histories: Incorporating the Orange Shirt

Although “beading treaty relations” (Allison, 2021) and “beading through Nbisiing Nishnaabeg histories” (Beaucage and Srigley, 2021) foregrounds methods of engaging with the past through art-creation, it is also important to recognize that the beaded installation is an example of history actively being made. This layered, ongoing form of history-making can be a profoundly emotional and uneasy process. During the stages of beading and organizing the installation, for example, mass graves of children were located at former residential school sites across the country through ground penetrating radar, confirming what Indigenous elders and community members had long known and expressed but with little state recognition in the past. In response, the project organizers decided to offer orange shirt kits to those who wished to incorporate a beaded orange shirt into their design.

Orange shirts have become a powerful symbol of the “Every Child Matters” movement, inspired by Phyllis Jack Webstad (Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation) whose favourite orange shirt was taken from her at residential school and whose story is honoured through Orange Shirt Day, now also known as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. The orange shirts symbolize the violence and forced assimilation of the Canadian Indian Residential School system while honouring children and survivors. The shirts are, therefore, a call to action.

The inclusion of orange shirts in the Lake Nipissing Beading Project was not originally part of the project design; however, it highlights an example of responding to history as it is being made (and, in so doing, actively making history through art). Beading the shirts into the lake provided a powerful outlet for participants to collectively mourn and honour the children and their families, acknowledge and condemn colonial violence and genocide, and hope and heal together (Fig. 7). Years from now, the map will signify a very specific historical moment and the multi-national reckoning that came with it, while also stitching together many other layers of ancestral, cultural, and environmental histories.

The project is intended to be ongoing, taking on new trajectories as it evolves. By the time this course is offered, it will have already changed shape, likely in ways we cannot anticipate. We will therefore not offer concrete “conclusions” about what it has meant to participants or the contributions it makes to the digital humanities, but instead invite you to explore it further through the maps, photographs, videos, and links on the project website.