Vol. 2, No. 1 (June 2024)

Using Amazon Mechanical Turk for Consumer Behaviour Research

Hamid Shaker and Ali Tezer

All figures in U.S. dollars unless otherwise noted.

Jade Charette-Côté, an M.Sc. student in marketing at a Canadian business school, had recently designed a survey for the data collection phase of her dissertation. Her aim was to complete the data collection by March 2021 and graduate in December 2021. Having finalized the stages of theorizing and conceptualization, she was ready to collect data and expected to replicate specific survey results based upon the supporting research for her study.[1] Given that she did not have access to a participant pool at her university, her supervisor suggested that she collect data online through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), a crowdsourcing platform that had become widely used in scholarly research.[2]

Excited to collect the first set of data for her dissertation, she prepared an experimental study on the online survey platform Qualtrics and ran the study on MTurk following her supervisor’s suggestion. The results, however, were discouraging because she was not able to replicate the expected findings. She was very disappointed with these results and wondered what had gone wrong. Did she make a mistake while designing the survey on Qualtrics? Did she not use appropriate communications strategies for MTurk? Considering the time needed to analyze the results and write the dissertation, she had only four weeks to redesign the survey, collect the data, and analyze the results if she wanted to graduate in December. Realizing that she had underestimated the dynamics of MTurk, she needed to determine the best strategy to redesign her survey quickly to increase its reliability. But where should she start?

Charette-Côté’s Data Collection: Background Information

After spending a considerable amount of time theorizing and conceptualizing her research idea, Charette-Côté proceeded to collect the initial data for her dissertation, aiming to test the effect of personal control on brand preference. Following her supervisor’s suggestion, she prepared a survey with two objectives: (1) to replicate the effect that had been demonstrated in a 2020 study by Beck, Rahinel, and Bleier, and (2) to use an individual difference variable to test the boundary conditions of that study.[3]

Charette-Côté intended to extend the work of Beck, et al. (2020), in which they had hypothesized consumers who felt that they had low personal control would prefer a brand that was the leader in the product category over a brand that is the follower. Beck and colleagues also hypothesized that this effect would disappear for consumers who felt that they had high personal control. The data collected by these researchers had supported their hypotheses.[4]

To examine these relationships, Charette-Côté crafted an experimental study adopting the stimuli and procedure outlined in Beck et al. (2020). The study employed a 2 (personal control: low, high) × 2 (desirability for control: measured) between-participants design. Due to the unavailability of a participant pool at her university, she sought an external pool. While exploring various solutions, she noticed that many of the research articles she had referenced during the literature review had recruited participants via MTurk. Discussing this with her supervisor, who regularly engaged with the same platform for diverse research projects, led to his recommendation to use MTurk for participant recruitment.

MTurk: A Game Changer

At the time of the case, MTurk was an online labour market that was owned and operationalized by Amazon and connected employers (i.e., requesters) with potential workers. Through this platform, MTurk workers (Turkers) could complete tasks referred to as “human intelligence tasks” (HIT) that were conceived by requesters. HITs were usually small repetitive tasks that humans could perform without requiring them to have any specific knowledge or training. Requesters defined a project, choose the compensation amount, specified the qualifications that Turkers should have, and launched the project. After the launch, potential Turkers saw the tasks available, chose the ones they intended to complete, and then submitted the HIT. Finally, requesters reviewed the submitted HITs and either accepted or rejected the submission. Amazon received a commission on the basis of the wage paid.

One of the common types of HITs in MTurk were surveys. Scholars, including consumer behaviour researchers, used MTurk to recruit participants to take their surveys or complete experiments. To do this, researchers posted HITs that linked Turkers to online research platforms such as Qualtrics, and Turkers completed them on a first-come, first-served basis. After finishing the task, the researchers could review the task and once their work was approved, participants were paid by the researchers.

The pool of participants in MTurk was large. Although Amazon did not report official numbers, researchers had estimated that there were between 250,000 and 750,000 Turkers, mostly U.S. residents.[5] According to a survey of Turkers by the Pew Research Center[6], 50% of respondents spent 10 hours per week completing HITs, and about 63% of them checked the website every day to find and complete the tasks. However, less than half of them made more than $5 per hour, and less than 10% made more than $8 per hour. In terms of demographics, those who considered MTurk as only part of their income and had another job tended to be younger and more educated than those who considered their MTurk work a full-time job.

Given the central role of data in consumer behaviour research, it did not take long for MTurk to catch the attention of consumer behaviour scholars as a tool to recruit research participants. Compared to the other conventional data collection tools, such as student samples, MTurk allowed easy access to a large pool of participants with a diverse demographic composition.[7] Another factor that made MTurk appealing to many scholars was its convenience and cost effectiveness: Scholars could quickly collect data on MTurk at a cost that was significantly lower than other recruitment methods.[8]

It was also noteworthy that the research designs scholars implemented in MTurk involved not only online experiments but other methods, such as longitudinal surveys and observations. Despite its advantages, scholars had raised numerous concerns regarding the use of MTurk for academic research and had questioned the validity of experiments conducted through the platform.[9] In a 2021 article, Aguinis and colleagues had reported the major concerns regarding the use of MTurk in scholarly research. See Exhibit 1 – Issues Scholars Face on MTurk that Threaten Study Validity.

Data Collection

Charette-Côté had limited experience in collecting data through MTurk or similar online platforms. In her brief exchanges with peers, she discovered that numerous students used MTurk after setting up their online studies via Qualtrics, which was the university-provided platform for setting up online surveys. One classmate cautioned her about Turkers who might respond without thoroughly reading the questions, and advised Charette-Côté to incorporate certain questions that could filter genuine participants from those randomly answering queries.

Charette-Côté prepared her survey on Qualtrics. The survey began with an attention check, following the suggestion of Oppenheimer et al. (2009).[10] This was a procedure commonly used in MTurk studies and the same procedure that her supervisor had used in a previous experiment. After the attention check question, participants were exposed to the personal control manipulation. In the survey, personal control was manipulated using a writing task, a commonly used approach.[11]Half of the participants were asked to describe a threatening or scary incident where they felt like they had no control over the outcome (i.e., low-control condition), the other half of the participants were asked to describe a threatening or scary incident where they felt like they had complete control over the outcome (i.e., high-control condition). After the personal control manipulation, the dependent variable was measured using a dichotomous choice between a $25 gift card from McDonald’s (product category leader) or a $25 gift card from Wendy’s (product category follower).[12] Finally, the participants were asked to complete the desirability for control scale, which was the measured individual difference variable and provided demographic information. See Exhibit 2 – Charette-Côté’s Survey for the MTurk Study.

Once the survey was ready, Charette-Côté used her supervisor’s MTurk account to run the study. Her supervisor had used MTurk previously and treated the workers fairly and therefore had good ratings in the online forums that MTurk workers use to evaluate researchers. Charette-Côté estimated that the task would take about seven minutes to complete. While configuring the compensation amount, she decided to offer $2 per participant for the task, aiming to expedite data collection and encourage participants to engage more attentively with the questions. She decided to be available online during the data collection to answer participants’ questions. The data collection was completed without any problems.

As soon as the data collection was complete, Charette-Côté checked how many participants had quit the survey before completing it and found there were only a few. When she looked at the data, however, she was surprised, as the results were not as expected. The inferential statistical tests revealed no significant effect of personal control manipulation on gift card preference, hence the effect demonstrated by Beck, Rahinel, and Bleier in 2020 had not been replicated. Furthermore, there were no significant interaction effects between the personal control manipulation and the measure of desirability for control, meaning that her hypothesis extending the work of Beck et al. (2020) was not supported.

Charette-Côté accepted that her hypothesis may not have been supported by the results, but felt that there may be something wrong with the data, given that it did not replicate the findings of Beck et al. (2020). When she took a careful look at the data, she identified some unexpected patterns. First, she realized that there were some participants who wrote almost meaningless entries for the personal control manipulation. Second, she realized that many participants selected the same value for the items in the desirability of control scale, even though one item was reverse-coded; it should have been impossible for a respondent to strongly agree to a regular item and a reverse-coded item. These patterns made her question the quality of the data, but she could not be certain that this was the main issue, because almost all the participants had passed the attention check.

Moving Forward

Charette-Côté told her supervisor about the results of the study and shared her observations. They discussed the next steps and concluded that it was worth giving this study another shot, considering the unexpected patterns identified in the data. However, her supervisor strongly instructed Charette-Côté to investigate survey strategies to ensure a more effective use of MTurk for data collection and to implement additional precautions to avoid experiencing the same issues. Charette-Côté left her supervisor’s office with excitement, ready to research strategies to improve the design of her survey and was determined to meet the challenges posed by MTurk. As she walked back to her desk, she wondered which strategies she could use to improve the design and reliability of her survey.

Exhibits

Exhibit 1 – Issues Scholars Face on MTurk that Threaten Study Validity

| Challenge | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Turker inattention | Turkers may complete a survey without paying attention to the instructions and/or the questions. | Participants may randomly answer questions in order to finish a survey quickly. |

| Self-misrepresentation | Turkers misrepresenting their profile in order to be eligible to complete attractive HITs with screening criteria. | Male participants may indicate their gender as female so that they can participate in a survey that is only for females. |

| Self-selection bias | The pool consists only of people who have decided to participate in surveys on MTurk. | Turkers oversampling HITs with high compensation. |

| High-attrition rate | Turkers who begin a HIT often fail to complete the study. | More than 40% of Turkers who start a survey quit before finishing the survey |

| Inconsistent English-language fluency | Turkers may have varying degrees of competence in English language, which can influence the comprehension of the questions and instructions in a survey. | Participants not being able to understand the instructions provided for an experimental manipulation. |

| Turker non-naiveté | Turkers who frequently complete surveys become familiar with experimental paradigms. | An experimental manipulation becomes ineffective because the participants have been frequently exposed to the paradigm in the past. |

| Growth of MTurk online communities | Turkers share their experiences with surveys and researchers with each other in online communities. | Turkers may inform each other about how to pass the screening questions in a survey. |

| Vulnerability to web robots (i.e., “bots”) | Turkers may use programs that generate randomly distributed answers to surveys. | A researcher observes meaningless answers to open-ended questions in a survey. |

| Perceived researcher unfairness | Turkers may consider a researcher to be unfair depending on the amount of compensation, accuracy of stated time requirement, etc. | Turkers may boycott a researcher who consistently claims that a study takes less than the actual time needed to complete a survey. |

Source: Adapted from Aguinis et al., 2021.

[back]

Exhibit 2 – Charette-Côté’s Survey for the MTurk Study

Consumer Behavior Study

Purpose

The main purpose of the study is to understand how situational factors influence how consumers behave. The conclusions of this research are intended to be presented at international conferences and published in consumer behavior research journals.

Time and Questionnaire

For this survey you will be asked to imagine yourselves in a scenario and answer a series of questions about how you feel and might react. Since your first impressions best reflect your true opinions, we would ask that you please answer the questions included in this survey without any hesitation. There is no time limit for completing the survey, although we have estimated that it should take about 7 minutes and you will be paid $2 for your participation.

Risks and Participation

There are no known physical or economic risks associated with this survey. Some questions, however, might be personal in nature asking how you see and feel about yourself in general. If you feel uncomfortable at any point during the questionnaire, you can withdraw by simply closing your web browser containing the questionnaire. HEC Montréal’s Research Ethics Board has determined that the data collection related to this study meets the ethics standards for research involving humans. If you have any questions related to ethics, please contact the REB secretariat at (***) ***-**** or by email at ***@***.ca.

Information and Confidentiality

The only information we record about you is the answers you provide in the questionnaire. No other information is taken from your computer. You are not obliged to answer any questions that you find objectionable or which make you feel uncomfortable.

I understand that participation is completely voluntary and I can withdraw from this study without prejudice or penalty by simply discontinuing the survey by closing my web browser. I also understand that once I complete this study and send my data that neither I nor the researcher will be able to withdraw my data because it is stored anonymously.

I read and understood the information contained in this letter; I have had any questions answered to my satisfaction; I understand the expectations and requirements of the current study; and I will save a copy of this page for my records.

-

- I agree

- I disagree

Start of Block: Attention Check

Sports Participation

Most modern theories of decision making recognize the fact that decisions do not take place in a vacuum. Individual preferences and knowledge, along with situational variables can greatly impact the decision process. In order to facilitate our research on decision making we are interested in knowing certain factors about you, the decision maker. Specifically, we are interested in whether you actually take the time to read the directions; if not, then some of our manipulations that rely on changes in the instructions will be ineffective. So, in order to demonstrate that you have read the instructions, please ignore the sports item below, as well as the continue button. Instead, simply click on the title at the top of this screen (i.e., “sports participation”) to proceed to the next screen. Thank you very much.

Which of these activities do you engage in regularly? (Click on all that apply)

- Skiing

- Soccer

- Snowboarding

- Running

- Hockey

- Football

- Swimming

- Tennis

- Basketball

- Cycling

End of Block: Attention Check

Start of Block: Personal Control Manipulation

Randomized: [Low Personal Control Condition]

Please recall a threatening or scary incident in which you had no control and describe this incident in the space provided below:

Randomized: [High Personal Control Condition]

Please recall a threatening or scary incident in which you had complete control and describe this incident in the space provided below:

Start of Block: Gift Certificate Choice

In this study, you would be entered into a raffle for one of two $25 gift certificates to a restaurant. Participants whose MTurk ID is drawn in the raffle will receive a $25 gift certificate for one of the two restaurants: McDonald’s or Wendy’s.

Please choose which restaurant you would prefer if you received one of the gift certificates:

- McDonald’s

- Wendy’s

End of Block: Gift Certificate Choice

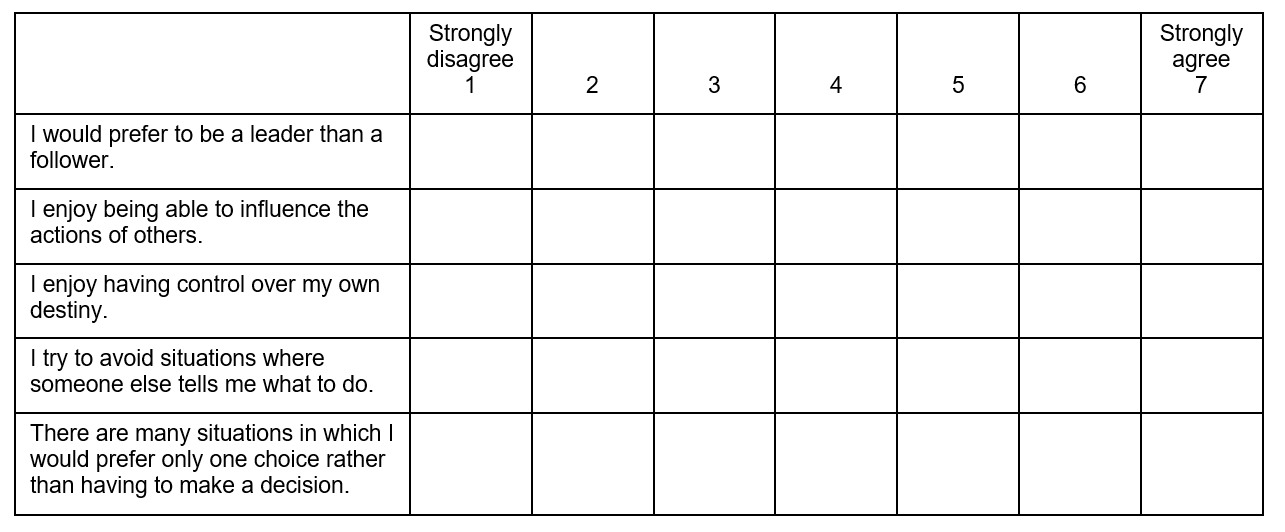

Start of Block: Desirability of Control

Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.

End of Block: Desirability of Control

Start of Block: Demographics

Please answer the following demographic questions.

Are you …

- Male

- Female

- Non-binary

How old are you?

How big is your household including you?

- 1 person (i.e., just me)

- 2 people

- 3 people

- 4 people

- 5+ people

What is your race/ethnicity?

- African-American or Black

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Chicano/Chicana

- Hispanic or Latino

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

- White

- Other, please specify

Which statement best describes your current employment status?

- Employed, working 1–39 hours per week

- Employed, working 40 or more hours per week

- Not employed, looking for work

- Not employed, NOT looking for work

- Retired

- Disabled, not able to work

- Not employed (other)

What is your annual income range?

- Below $20,000

- $20,000–$39,999

- $40,000–$59,999

- $60,000–$79,999

- $80,000–$99,999

- $100,000 or more

Please indicate your native language.

- English

- Spanish

- Chinese

Other:

End of Block: Demographics

Start of Block: Debrief

Debrief: This study was about understanding the influence of feelings of personal control and individual differences in desirability of control on consumer preference between brands who are product category leaders and followers.

Thank you for your participation.

End of Survey

Credit: © Jade Charette-Côté. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

[back]

Image Descriptions

Exhibit 2 – Table

An image of a blank Likert-scale survey formatted as a table with 8 columns and 6 rows. In the first row, the scale begins in column 2 with “strongly disagree 1” and ends in column 8 with “strongly agree 7.” The survey items listed in column 1 are as follows:

- I would prefer to be a leader than a follower.

- I enjoy being able to influence the actions of others.

- I enjoy having control over my own destiny.

- I try to avoid situations where someone else tells me what to do.

- There are many situations in which I would prefer only one choice rather than having to make a decision.

[back]

References

Aguinis H., Villamor I., & Ramani R.S. (2021). MTurk research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 47(4), 823–837.

Beck, J. T., Rahinel, R., & Bleier, A. (2020). Company worth keeping: Personal control and preferences for brand leaders. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(5), 871–886.

Goodman, J. K., & Paolacci, G. (2017). Crowdsourcing consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(1), 196–210.

Hitlin, P. (2016). Research in the Crowdsourcing Age, a Case Study. Pew Research Center.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872.

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163.

Porter, C. O., Outlaw, R., Gale, J. P., & Cho, T. S. (2019). The use of online panel data in management research: A review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 45(1), 319–344.

Robinson, J., Rosenzweig, C., Moss, A. J., & Litman, L. (2019). Tapped out or barely tapped? Recommendations for how to harness the vast and largely unused potential of the Mechanical Turk participant pool. PLOS ONE, 14(12): e0226394.

Sharpe Wessling, K., Huber, J., & Netzer, O. (2017). MTurk character misrepresentation: Assessment and solutions. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(1), 211–230.

Walter, S. L., Seibert, S. E., Goering, D., & O’Boyle, E. H. (2019). A tale of two sample sources: Do results from online panel data and conventional data converge?. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(4), 425–452.

Download a PDF copy of this case [PDF].

Read the Instructor’s Manual Abstract for this case.

How to cite this case: Shaker, H. & Tezer, A. (2024). Using Amazon Mechanical Turk for consumer behaviour research. Open Access Teaching Case Journal, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.58067/prvk-jt58

The Open Access Teaching Case Journal is a peer-reviewed, free to use, free to publish, open educational resource (OER) published with the support of the Conestoga College School of Business and the Case Research Development Program and is aligned with the school’s UN PRME objectives. Visit the OATCJ website [new tab] to learn more about how to submit a case or become a reviewer.

ISSN 2818-2030

- Beck et al., 2020. ↵

- Aguinis et al., 2021; Goodman & Paolacci, 2017; Porter et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2019. ↵

- Beck et al., 2020. ↵

- Beck et al., 2020. ↵

- Robinson et al., 2019. ↵

- Hitlin, 2016. ↵

- Goodman & Paolacci 2017; Peer et al., 2017. ↵

- Sharpe Wessling et al. 2017. ↵

- Aguinis et al. 2021; Goodman & Paolacci 2017; Robinson et al. 2019; Sharpe Wessling et al., 2017. ↵

- Oppenheimer et al. 2009. ↵

- See Beck et al., 2020. ↵

- This echoes Beck et al, 2020. ↵